|

Bobby Few

|

7 jan. 2021

|

|

21 octobre 1935, Cleveland, OH - 7 janvier 2021, Levallois-Perret (92), France

|

© Jazz Hot 2021

|

Bobby Few au Toucy Jazz Festival 2012 © Mathieu Perez

Bobby FEW

Comme un torrent

«Je sais tout jouer, alors ça ne sert à rien de me coller une étiquette!», lançait Bobby Few à Jazz Hot en 2002. Si, pendant longtemps, son expression artistique privilégiée était le free, que ce soit dans Center of the World, le sextet de Steve Lacy, ou ses associations avec Sunny Murray ou Henry Grimes, Bobby jouait le blues comme personne, connaissait tous les standards sur le bout des doigts, était toujours virtuose. Il décrivait son style comme un «mélange d’énergie et de romantisme». Qu’on écoute ses disques en leader ou en sideman, qu’on l’ait vu en concert avec son trio, composé d’Harry Swift et Ichiro Onoé, ou en sideman avec Ricky Ford, l’énergie et le lyrisme sont omniprésents. On pourrait ajouter une infinie élégance et gentillesse. Car Bobby est de ces musiciens qui ressemblent à leur musique. Fluet, souriant, la voix éraillée capable de bouleverser lorsqu’il chantait, car il chantait avec naturel sans faux effets, toujours vrai, avec son cœur et sa sensibilité.

Bobby s’est éteint le 7 janvier 2021, des suites d’une longue maladie. Il avait 85 ans, l’âge de Jazz Hot. Retracer son parcours, c’est traverser plus d’un demi-siècle d’histoire du jazz et des pages importantes du jazz en France. En dehors de cet hommage, il sera utile de se référer à l'intéressante interview de Bobby Few parue dans le Jazz Hot n°596 en décembre 2002 où se trouvent d'autres photographies de Bobby des années 1950 et 1960. Bobby participait régulièrement aux anniversaires de Jazz Hot et sa présence fragile nous manque déjà…

Mathieu Perez

Avec la participation des ami(e)s-artistes qui témoignent à la suite de ce texte

Nous remercions Simone Few, Chris Henderson et Syd Smart (photos et documentation)

Vidéographie Hélène Sportis

Photos Ellen Bertet, Alain Dupuy-Raufaste, Jérôme Partage, Mathieu Perez

© Jazz Hot 2021

Bobby est né le 21 octobre 1935 à Cleveland, dans l’Ohio. Moins célébrée que Philadelphie ou Detroit, cette ville a été, et est toujours, un terreau fertile pour le jazz. Elle nous a donnés Noble Sissle (1889-1975), Freddie Webster (1916-1947), Tadd Dameron (1917-1965), Henry Mancini (1924-1994), Little Jimmy Scott (1925-2014), Benny Bailey (1925-2005), Jim Hall (1930-2013), Bill Hardman (1932-1990), Albert Ayler (1936-1970), Joe Lovano (1952) ou encore Ken Peplowski (1959). Originaires de l’Ohio, il y a, bien sûr, Art Tatum (1909-1956), Rahsaan Roland Kirk (1935-1977) et Stanley Cowell (1941-2021).

Encore quelques repères: Bobby est le contemporain de Rashied Ali (1933), Steve Lacy (1934), Roswell Rudd (1935), Don Cherry (1936), Sunny Murray (1936), John Tchicai (1936), Archie Shepp (1937) ou Kirk Lightsey (1937). Une génération de musiciens connaissant parfaitement la tradition, et qui ont assimilé dans leur musique les innovations de John Coltrane (1926), Cecil Taylor (1929) et Ornette Coleman (1930).

Bobby a grandi à Fairfax, le quartier afro-américain de Cleveland, dans une famille méthodiste très pieuse. S’il dit son aversion pour l’Eglise, il a été marqué par la church music. Son père, Robert Few, Sr., est maître d’hôtel dans un country club ségrégationniste, à Pepper Pike. Sa mère, Winifred, est femme au foyer et violoniste en amateur. Bobby est fils unique. Il débute des études de piano classique à l’âge de 7 ans. Il apprend au côté de Kathleen Holland Forbes, l’organiste de la St. James African Methodist Episcopal Church. Bobby découvre le jazz en écoutant les disques de son père, notamment Jazz at the Philharmonic. Il apprend le blues et le boogie-woogie, dont il joue, pour titiller sa prof’ de piano classique, avant la leçon. «Je n’ai pas abandonné la musique classique, le jazz s’est simplement emparé de moi: il a jailli du piano comme le génie de la lampe d’Aladin!»1 Bobby étudie à la John Adams High School et poursuit ses études de piano classique au Cleveland Institute of Music. A 15 ans, il participe au groupe The Young Nobles qui manifesta plusieurs semaines durant devant la East Technical High School, alors ségrégationniste, pour l’ouvrir aux Afro-Américains. Un succès.

Bobby est un talent musical porté par son père qui l’encourage et lui trouve des engagements dès l’adolescence. Il joue avec son copain d’enfance Albert Ayler dans des bouges, se produit avec les aînés, notamment le trompettiste Bill Hardman et le contrebassiste Bob Cunningham, son cousin. Lequel lui présente des musiciens fameux, comme John Coltrane, avec qui il fait le bœuf chez Cunningham.

Bobby Few (au centre) Trio

avec Raymond Farris (dm) et Cevera Jeffries (b), c. 1955-1960

© photo X, Collect. Bobby et Simone Few by courtesy

A la question des premières influences, Bobby cite Erroll Garner, Art Tatum (qu’il a vu en concert) et Monk. Il raconte aussi trois anecdotes fameuses. La première se déroule à un concert de Bud Powell au Loop Lounge, club important de Cleveland. Le jeune Bobby remarque que Bud semble mâcher du chewing-gum pendant toute la soirée. Il lui pose la question. Celui-ci lui répond qu’en fait, il fredonne la musique avant de la jouer. Et il lui conseille d’en faire autant.2 La seconde anecdote se passe au Cotton Club, à Cleveland. Bobby jouait alors à l’entracte pendant le concert d’Ella Fitzgerald. Laquelle salue le talent du jeune homme: «Ladies and Gentlemen, his name might be Few but he plays a lot!». Tommy Flanagan accompagnait Ella. Lorsque Bobby lui demande s’il peut venir chez lui pour lui montrer deux ou trois trucs au piano, Tommy Flanagan accepte volontiers.2 Dernière anecdote: lors d’un concert de Miles Davis, Red Garland laisse sa place à Bobby pour «Walkin’». Mais il le joue en si bémol et non pas en fa comme le lui souffle Paul Chambers…1 Autant de leçons et de conseils que les aînés donnent au jeune homme.

Dans ces années-là, Cleveland est une scène jazz très active. Les musiciens en tournée s’y arrêtent. Prenez le Loop Lounge, par exemple, un des grands clubs de la ville. En 1955, y sont passés Lester Young, James Moody, Max Roach & Clifford Brown, Oscar Peterson (avec Ray Brown et Herb Ellis), Earl Hines, Stan Getz & Bob Brookmeyer, Illinois Jacquet, Roy Eldridge, Ben Webster (avec Howard McGhee et Hank Jones), Erroll Garner ou encore Dizzy Gillespie.3 Le jeune Bobby a aussi vu Charlie Parker en concert, peut-être en compagnie d’Albert Ayler. Bird encourage le jeune pianiste à jouer sa propre musique.4

En 1955, Bobby a 20 ans. Il monte le East Jazz Trio, avec le contrebassiste Cevera Jeffries, avec qui il partira à New York, et le batteur Raymond Farris. Le groupe connaît un grand succès à Cleveland.

Ici, un détour par Albert Ayler est nécessaire 5. En 1956, Ayler quitte sa ville natale. Il part faire son service militaire à Fort Knox, dans le Kentucky, et passe de l’alto au ténor. En 1959, il est transféré en France où il intègre à son répertoire et à sa façon quelques marches et éléments de folklore. Deux ans plus tard, renvoyé à la vie civile, il s’installe à Los Angeles, puis revient à Cleveland. Son nouveau style répugne la plupart des patrons de club et des musiciens locaux. Seul Roland Kirk accepte de jouer avec lui. En 1962, il part pour Stockholm. C’est là qu’il rencontre Cecil Taylor qui tourne en Europe avec son trio, composé de Jimmy Lyons (as) et Sunny Murray (dm). Ayler intègre la formation. De retour à New York, la formation de Cecil Taylor, avec Henry Grimes, joue au Take Three où Coltrane et Eric Dolphy viennent les voir plusieurs fois. En 1963, ne parvenant pas à gagner sa vie, Ayler repart à Cleveland où il se lie avec Frank Wright, alors contrebassiste, et lui transmet ce qu’il a appris de Cecil Taylor. Plus tard dans l’année, Ayler retourne à New York et travaille avec Ornette Coleman.6 Les trajectoires d'Albert Ayler et de Bobby Few sont marquées par la musique de Cecil Taylor. Ce serait par l’intermédiaire de Frank Wright que Bobby va aborder le langage de Cecil Taylor. Après les influences d’Erroll Garner, Art Tatum et Thelonious Monk, il va commencer à opérer une synthèse personnelle à partir des idées musicales de John Coltrane7, Cecil Taylor8 et Ornette Coleman9. Sa période new-yorkaise est décisive.

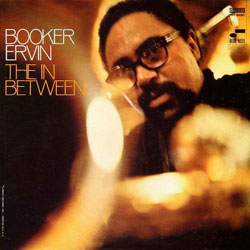

Bobby s’est installé à New York grâce à Albert Ayler, son ami d’enfance avec qui il jouait au baseball qui ne cessait de le lui conseiller. Bobby a dû faire des allers-retours entre 1958 et 1962 avant de s’y fixer pour de bon, difficile de trouver les dates exactes. Bobby travaille avec Bill Dixon au sein du Marzette Watts Ensemble avec lequel il enregistre, le big band de Frank Foster, Roland Kirk… Bobby parle de cette période en termes poétiques: «Ma musique avait changé: j’avais fait un rêve où je voyais ma musique comme un ouragan, un tourbillon qui emportait tout sur son passage. J’ai fait en sorte de développer un style qui corresponde à cette vision.»1 Il vit alors dans un immeuble du Lower East Side. Ses voisins sont Randy Weston et Booker Ervin. C’est en l’entendant jouer du piano que le ténor décide de l’embaucher pour enregistrer The In-Between, pour Blue Note.

En 1968, Bobby rencontre le saxophoniste alto Noah Howard (cf. Jazz Hot n°257-1970, n°326-1976, n°605-2003). Peu de temps après, Howard et Frank Wright forment un quartet avec Bobby et Muhammad Ali. Est-ce cette formation qui s’est produite au Slugs’ sous le nom du leader Frank Wright? Les infos manquent. Ce qui est sûr, c’est que ce groupe jouait « au Café La Mamma, à New York, tous les lundis, de 8h à minuit.» 10 Avant d’arriver en Europe, ils se connaissent tous très bien musicalement.

En 1969, de retour d’une tournée avec le chanteur Brook Benton –Bob Cunningham (b) et Leroy Williams (dm)– qui l’a emmené en Jamaïque, à Londres et en Ecosse, après avoir enregistré avec Albert Ayler, Bobby et le reste du Wright-Howard Quartet décident de partir pour la France, l'horizon et la vie étant trop bouchés à New York. Le quartet est programmé au Festival d’Amougies (24-28 octobre), en Belgique, organisé par la revue Actuel. Bobby se produit le deuxième soir. Parmi les spectateurs, il y a notamment Steve Lacy, subjugué par le jeu de Bobby. La formation joue dans d’autres festivals, à Amsterdam et Rotterdam, puis jette l’ancre à Paris.

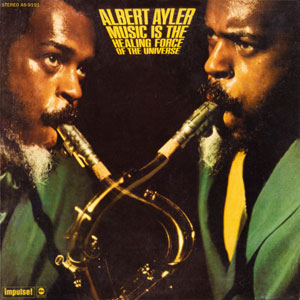

Quelques mois plus tôt, en août 1969, Bobby a enregistré avec Albert Ayler, Music Is The Healing Force of the Universe, pour Impulse!. En plus d’Ayler et Bobby, la formation se compose de Mary Maria (Parks) (voc), Henry Vestine (g), Stafford James (b), Bill Folwell (b, eb), Muhammad Ali (dm). Il y a eu deux sessions d’enregistrement. Les thèmes ne figurant pas dans ce disque sortent dans The Last Album. Deux disques démolis par la critique. Outre deux beaux moments free dans The Last Album avec «Birth Mirth» et «Water Music», il y a un thème de Music Is the Healing Force of the Universe où on sent Ayler et Bobby particulièrement complices: «Drudgery», un blues, qui conclut le disque, et renvoie le ténor et le pianiste aux gigs de leur adolescence dans les bouges de Cleveland. Se sont-ils revus après cela?

Le 25 novembre 1970, Ayler est retrouvé mort, son corps flottant dans l’East River, à Brooklyn. Les circonstances de sa mort demeurent méconnues. Un memorial concert est organisé au Karamu House –le plus ancien théâtre afro-américain des Etats-Unis– à Cleveland, en avril 1971. Bernard Lairet, un correspondant de Jazz Hot, est sur place: «J’étais le seul Blanc aux funérailles d’Albert Ayler, et profondément choqué de n’y voir qu’une vingtaine de personnes; les proches amis, mais aucun membre du jazz business, aucun musicien.»11 Le 11 avril 1971 était un dimanche: «à 3 heures, débuta ce qui fut plus qu’un simple concert, mais plutôt une sorte de «gospel» qui ne s’acheva que vers 9 heures du soir. Je sais que vous n’êtes sans doute pas familier avec l’émouvante expérience d’une église noire un dimanche matin, mais essayez d’imaginer une assistance subjuguée, réagissant à la musique, aux poètes et aux danseurs comme elle le fait au «preacher»! Ce fut un spectacle d’une étonnante qualité, dont le sommet fut le fantastique "Bobby Few & the Sound Bomb": 28 musiciens, 5 ténors, 4 altos, 1 baryton, 4 trompettes, 1 trombone, 1 flûte (électrique, heureusement), 5 bassistes, 1 violoncelliste, 2 drummers, 1 percussionniste, 1 conga!!!» Cette formation ne joue qu’un seul thème: une composition de Bobby intitulée «Strange Song», articulée en trois parties. Et Lairet de préciser: «Few ne put jouer que quelques notes sur le piano, ayant à diriger l’orchestre d’un étonnant ballet de gestes.» Le soir même, Lairet assiste à un «soul festival» à Cleveland où se produisent Bobby, Frank Wright, Norris Jones et Muhammad Ali.

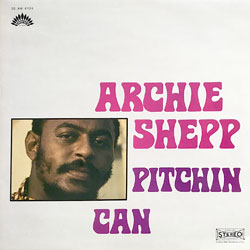

La direction d’orchestre est une voie que Bobby ne poursuivra pas, même s'il a un talent particulier pour l'arrangement dont parlent tous ses amis musiciens, dont Alan Silva. Il est pris par d’autres activités. Il a déjà rencontré Archie Shepp et déjà enregistré avec lui un album, Pitchin Can dès la fin des années 1960. En France, Bobby Few va écrire une page importante de l’histoire du free jazz avec Center of the World, un collectif créé avec Alan Silva et Muhammad Ali auquel se joint Frank Wright. Le collectif, à l'image de ce que nous avons vu pour Strata-East à la même époque ( cf. la nécrologie de Stanley Cowell, Jazz Hot 2021, et Charles Tolliver, Jazz Hot n°677), va autoproduire et autodistribuer des enregistrements, et c'est sur ce label que Bobby Few publie son premier enregistrement en leader ( More or Less Few, 1973) et en coleader avec le collectif ( Center of the World et Last Polka in Nancy?, 1972). En 1970, Bobby rencontre Simone, la femme de sa vie, qu’il épouse deux ans plus tard. En 1974, naît leur fils Cyril.

Mais Bobby Few n'est pas le seul à traverser l'océan, reproduisant la démarche des années 1930 des aînés Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Coleman Hawkins, Benny Carter, etc., ou celle de l'après guerre avec Don Byas, Dexter Gordon, Kenny Clarke, Sidney Bechet, Hal Singer, Johnny Griffin, jusqu'à Don Cherry en 1965… Paris est alors toujours un phare qui fait espérer la reconnaissance de la création nouvelle (le free jazz cherche une visibilté) et la Scandinavie a ajouté de l'attrait à ce phare, parce qu'aussi la vie y semble moins bornée par le racisme qui atteint une dimension de guerre civile aux Etats-Unis avec l'assassinat de Martin Luther King, Jr. et les émeutes à répétition faisant suite à cette tragédie. A la fin des années 1960 et au début des années 1970, d’autres «partisans» du free jazz et/ou des esthètes de la musique improvisée ont posé leurs valises à Paris: Sunny Murray en 1969, Anthony Braxton en 1969 (de l’AACM; reparti en 1970), Roscoe Mitchell, Joseph Jarman, Malachi Favors et Lester Bowie (de l’AACM, réunis sous le nom d’Art Ensemble of Chicago) en 1969 rejoint par Famoudou Don Moye et Steve Lacy en provenance de Rome (cf. le témoignage de Don Moye plus bas), Steve Potts en 1970, Oliver Lake, Julius Hemphill, Floyd LeFore (Black Artist Group), Joseph Bowie (de l’AACM) en 1972, etc. Toutes les motivations de cet exode d'artistes ne sont pas identiques: elles peuvent être personnelles, artistiques et politiques, mais elles ont un fond commun que nous avons déjà évoqué: la réalité politique aux Etats-Unis entre guerre du Viêt-Nam, émeutes sur fond de racisme, création dans le jazz soumise au rouleau compresseur de l'industrie musicale de consommation de masse, les artistes et intellectuels ayant plus de facilités à émigrer que le reste des Américains.

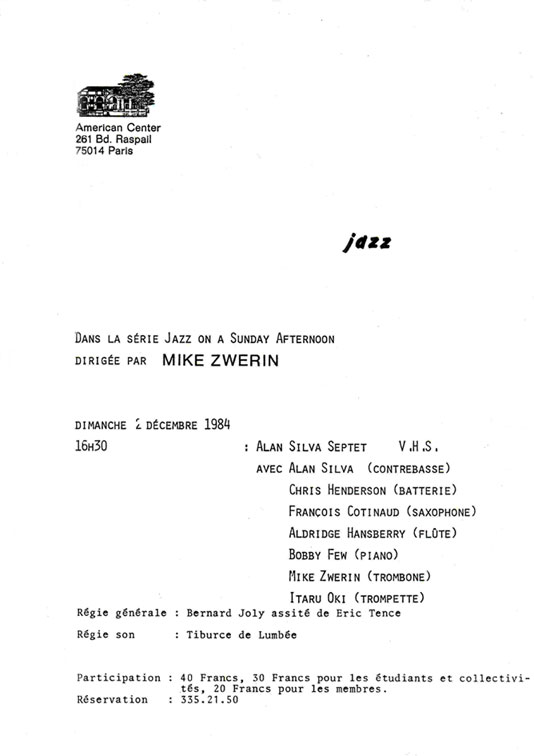

Programme du 2 décembre 1984 à L'American Center

sous la direction de Mike Zwerin, avec le Septet d'Alan Silva où joue Bobby Few

by courtesy of Chris Henderson

Bobby les côtoie, travaille et enregistre avec eux. L’American Center est leur quartier général. «A cette époque, l'American Center était très important. Nous nous sentions libres là-bas. Tout le monde l'utilisait comme un espace de répétition, un lieu d’échanges et de performances.», se souvient Steve Lacy.12

Center of the World, c’est Frank Wright, Alan Silva (qui remplace Howard), Bobby et Muhammad Ali. De 1969 à 1978, le groupe sort huit disques. Une musique tendue qui relève d'une autre civilisation et ne laisse pas indifférent, même les amateurs de jazz; et où on sent la place essentielle de Bobby. Il sait canaliser l’énergie de Wright et l’amplifier. Bien que marqué par Cecil Taylor, il a gardé sa voix personnelle, élégante, lyrique. Sous le même nom, Center of the World produit certains de leurs enregistrements et d’autres projets en leader, dont le premier disque de Bobby, More or Less Few, en 1973.

Il sort d’autres disques en leader et coleader: Solos and Duets (avec Alan Silva et Frank Wright, Sun Records, 1975), en deux volumes, Few Coming Thru (avec Alan Silva et Muhammad Ali, Sun Records, 1977) et Continental Jazz Express (Vogue, 1979). Bobby jongle avec les styles, expérimente, enregistre des blues («Few’s Blues»), un boogie-woogie («Few’s Boogie»), essentiellement des compositions personnelles («Continental Jazz Express»). Il chante aussi. Ses disques sont gorgés de feeling, de virtuosité, mais reflète aussi l'engagement radical d'une autre période dans l'art et la société, une volonté de créer une musique absolument personnelle. Une réédition s'impose!

Center of the World se sépare en 1978. Durant cette période, Bobby donne des cours à de jeunes musiciens. Parmi eux, le pianiste Patrick Villanueva: «J’ai étudié avec Bobby à peu près pendant un an, en 1979-1980. J’avais 17 ans, et j’allais chez lui assez régulièrement, à Levallois-Perret», raconte-t-il à Jazz Hot. «C’est Sophia Domancich, ma prof’ au Conservatoire du Xe arrondissement, qui m’avait donné son numéro de téléphone.»

Patrick parle de cette rencontre avec émotion: «C’étaient les années de ses disques Few Coming Thru et Continental Jazz Express, que j’écoutais en boucle. Il écrivait des chansons aussi, qu’il avait en projet d’enregistrer dans un format plus pop. Bobby m’a appris quelques trucs basiques, les enchainements d’accords par exemple, mais aussi comment jouer du piano comme d’une percussion. Et surtout on travaillait ses compositions et celles de Steve Lacy avec qui il commençait à jouer. Ça a été formidable pour moi de rencontrer un musicien qui abordait la tradition du jazz de façon tout à fait libre. Et, en plus, de m’avoir «autorisé» à devenir compositeur. Je garde le souvenir d’une relation humaine simple et de son enthousiasme pour la musique et le piano.»

Steve Lacy est l’autre grande aventure de la vie de Bobby. Entre 1980 et 1994, le sextet enregistre 17 disques. Il se compose de Steve Potts, Jean-Jacques Avenel (qui remplace Kent Carter), Oliver Johnson (remplacé par John Betsch en 1989), Irène Aebi (vln, voc), et Bobby, que Lacy voulait depuis longtemps: « L’une des raisons pour lesquelles je suis venu à Paris est que j’ai entendu ce groupe (Center of the World) lors d’un festival à Amougies en 1969. Je me suis dit: "Wow, c'est le pianiste que je cherchais". J'ai été fou de Bobby tout de suite. Il a été le premier pianiste que j'ai entendu après Cecil (Taylor) qui avait quelque chose à dire. D'autres personnes avaient des petites touches ici et là et des petites choses intéressantes. Mais lui était un pianiste qui avait son propre jeu post-Cecil et n'était pas raccroché à Cecil. En fait, il n’était accroché à rien. Il était totalement original et très bien développé. Mais il travaillait avec Frank (Wright) et je ne l'ai pas eu pendant dix ans.» 13Le leader ne tarit pas d’éloges sur ses musiciens: « Je suis très chanceux. J'ai une section rythmique fantastique (Bobby Few, Avenel et Johnson), ces gars sont incroyables. Ils jouent ensemble depuis tant d’années, mais au cours des deux dernières années, cela s’est encore amélioré. C'est vraiment juste maintenant. J’apprends d’eux. Je veux dire, ils ont plus de rythme que moi, c’est sûr. Monk m'a donné un bon conseil il y a de nombreuses années: fais en sorte que la rythmique sonne bien avec ce que tu joues.» 14 Cette intensité, cette recherche créative permanente, le documentaire Steve Lacy, Lift the Bandstand, réalisé par Peter Bull en 1985, les saisit dans plusieurs séquences musicales filmées.

Bobby Few, Espace Julien, Marseille 25 octobre 1984 © Ellen Bertet

Bobby Few, Espace Julien, Marseille 25 octobre 1984 © Ellen Bertet

Dans les années 1980, Bobby est très actif en leader. Selon qu'il soit à Paris ou en tournée, sa formation, trio ou quartet, peut varier, et compte la plupart du temps Chris Henderson, un batteur exceptionnel. Bobby Few et son groupe est la formation maison (house band) quand le Duc des Lombards devient en 1984 un club de jazz, avec son décor de brasserie ancienne, malheureusement disparu aujourd'hui, d'abord sous la houlette de Salah Mahjoub puis de Didier Nouyrigat. La communauté musicale du jazz et particulièrement américaine de Paris en fait un haut lieu du jazz dans les années 1990.

Bobby Few et Chris Henderson, Duc des Lombards, c.1986-1988

© photo X Collection Chris Henderson by courtesy

En 1985, Bobby forme également un duo avec Harry Swift; il joue en trio avec Jack Gregg et Chris Henderson, puis avec Raymond Doumbé et Noel McGhie en 1988, puis Harry Swift et Noel McGhie, enfin Harry Swift et Ichiro Onoé en 2003. Ce trio est parfois augmenté de Jon Handelsman (ts, fl, cl) et Rasul Siddik (tp). Il se produit dans les clubs, tourne dans les festivals européens. Bobby se lie aussi avec le ténor Avram Fefer, avec lequel il enregistre quatre disques, et Ricky Ford, installé à Paris en 1990-1991. En 2000, Bobby se produit en solo au New York Vision Festival. Un récital enregistré et sorti sous le nom Continental Jazz Express (Boxholder, 2002). Son quatrième enregistrement en solo, avec Few Coming Thru (Sun Records, 1977), Mysteries (Miss You Jazz, 1992), et Lights and Shadows (Boxholder, 2004). Bobby a aussi été invité en 2001 au Vision Festival avec Frank Wright Center of the World (Alan Silva, Noah Howard, Bobby Few, Leroy Williams).

Rasul Siddik en ombre chinoise de Bobby Few lors de l'hommage à Gérard Terrones, 10 décembre 2017, Sunset-Sunside © Mathieu Perez

Lorsque Jazz Hot avait demandé à Bobby s’il ne s’était pas radouci, comme Archie Shepp, il avait répondu qu’il ne s’agissait «pas tant de se radoucir que de retourner aux racines de (sa) musique.» On comprend ce qu’il voulait dire. Il suffisait de le voir en concert, jouer «Tyra» (enregistré avec Booker Ervin dans The In-Between), «Tapestry From An Asteroid» de Sun Ra, chanter son «Let It Rain», se lancer dans un thème de Duke Ellington. Sa musique n’avait jamais été aussi pleine de feeling, de générosité, de chaleur, de lyrisme.

Bobby était plus discret sur la scène jazz ces dernières années, mais il était un habitué du Toucy Jazz Festival, créé par Ricky Ford. Il s’y est produit de nombreuses fois, aussi bien en vedette en 2012 que lors de concerts intimistes (en solo ou en duo) à la galerie d’art de Ricky. Lequel, poursuit son work in progress d’adapter pour un big band les compositions de Bobby, comme il l’a fait pour Ran Blake, Amina Claudine Myers, Abdullah Ibrahim, Steve Lacy, Dave Burrell, Mal Waldron ou encore Mary Lou Williams.

Bobby Few et Hal Singer au Sunset-Sunside, 2 décembre 2010, une rencontre symbolique de l'histoire du jazz à Paris © Jérôme Partage

Bobby Few et Hal Singer au Sunset-Sunside, 2 décembre 2010, une rencontre symbolique de l'histoire du jazz à Paris © Jérôme Partage

En 2017, Bobby apparaît dans deux autres films. Le premier est un documentaire que Nicolas Barachin lui a consacré: Bobby Few, The Musical Hurricane. Le second, A Great Day in Paris, est un documentaire réalisé par Michka Saäl, sur les musiciens de jazz afro-américains vivant à Paris (Ricky Ford, Kirk Lightsey, John Betsch, Bobby Few, Sangoma Everett).

Cet été 2017, Bobby participe au 241e anniversaire de l'Indépendance des Etats-Unis et du centenaire de l'entrée des Etats-Unis dans la Grande Guerre, organisé par l’Ambassade des Etats-Unis. Un hommage aux Harlem Hellfighters du 369e régiment d’infanterie, du lieutenant James Reese Europe. C'est en musique, avec l'Original Paris James Reese Europe Commemorative Orchestra, dirigé par Ricky Ford. Cette mémoire-là est conservée. Reste à préserver, comme le rappelait Bobby à Jazz Hot, celle des musiciens afro-américains qui vivent, ou ont vécu, à Paris depuis les années 1960: «Mon souhait est que Paris n’oublie pas ce qu’elle a été. Il ne faut pas laisser s’éteindre une génération qui a fait son histoire. Paris oublie la musique improvisée.»1

Jazz Hot partage la peine de Simone et de la communauté du jazz à Paris de tous les horizons, qui perd avec Bobby Few, un «centre de son monde». Une cérémonie a eu lieu au Père Lachaise en présence de la famille et des proches.

3. Joe Mosbrook, «Jazzed in Cleveland», WMV Web News Cleveland, 2004

4. Joe Mosbrook, Cleveland Jazz History, Northeast Ohio Jazz Society, 2013

5. Albert Ayler dans Jazz Hot: n°213, 222, 268, 273, 381, 479, Spécial 2001 (discographie détaillée)

6. Jeff Schwartz, Albert Ayler, His Life and Music, e-book, 1992

7. John Coltrane dans Jazz Hot: n°182-1962, 234-1967, 491-1992, 492-1992

8. Cecil Taylor dans Jazz Hot: n°228-1967, 248-1969, 307-1974, 381-1981

9. Ornette Coleman dans Jazz Hot: n°193-1963, 205-1965, 281-1972, 302-1974, 323-1976, S1996-1996

10. François Postif, «The Noah Howard-Frank Wright Quartet», Jazz Hot n°257, 1970

11. Bernard Lairet, «Albert Ayler Memorial Concert», Jazz Hot n°273, 1971

12. Etienne Brunet, interview préparatoire aux liner notes pour la réédition de trois disques de Lacy, Roba (1969), Dreams (1975), The Owl (1977), chez Saravah, in Steve Lacy, Conversations, 34 interviews entre 1959 et 2004, dir. Jason Weiss, Duke University Press, 2006: «In that period, the American Center was very important. We felt free there. Everyone used it as a rehearsal space, a place to meet and perform.»

13. Christoph Cox, The Wire, 2002, in Steve Lacy, Conversations, op. cit.: «One of the reasons I moved to Paris was that I heard this group at a festival in Amougies in ’69. I said, «Wow, that’s the piano player I’ve been looking for». I was crazy about Bobby right away. He was the first pianist I heard after Cecil (Taylor) that had something to say of his own. Other people had little wrinkles here and there, and some little things that were interesting. But he was a pianist that had his own thing post-Cecil and was not hung up on Cecil. In fact, he wasn’t hung up on anything. He was totally original and very well developed. But he was working with Frank (Wright) and I didn’t get him for ten years.»

14. Kirk Silsbee, Cadence, 1988, in Steve Lacy, Conversations, op. cit.: «I’m very lucky. I have a fantastic rhythm section (Bobby Few, Avenel, and Johnson), these guys are amazing. They’ve been playing together for so many years but in the last couple of years it’s gotten even better. It’s really just right now. I’m there to learn from them. I mean, they got more rhythm than I do, that’s for sure. Monk gave me some good advice many years ago: make the rhythm section sound good with what you play.»

|

DISCOGRAPHIE

par Yves Sportis

Leader-coleader

LP 1972. Frank Wright/Bobby Few/Alan Silva/Muhammad Ali, Center of the World, Center of the World 001 (=CD Fractal 006 sous le nom de Frank Wright) LP 1973. Frank Wright/Bobby Few/Alan Silva/Muhammad Ali, Last Polka in Nancy?, Center of the World 002 (=CD Fractal 007 sous le nom de Frank Wright)

LP 1973. Bobby Few, More or Less Few, Center of the World 003 (2 visuels pour le même disque)

LP 1975. Bobby Few/Alan Silva/Frank Wright, Solos Duets, Sun Records 102/CW 006 LP 1975. Bobby Few/Alan Silva/Frank Wright, Solos Duets, Sun Records 103/CW 006 LP 1977. Bobby Few, Few Coming Thru, Sun Records 001

LP 1979. Bobby Few, Continental Jazz Express, Jazz Today 5/Vogue 2605

LP 1979. Bobby Few/Cheikh Tidiane Fall/Jo Maka, Diom Futa, Free Lance 001

LP 1983. Bobby Few, Black Lion 65111 CD 1991. Bobby Few, Few and Far Between, Adès 941 982 CD 1992. Bobby Few, Mysteries, Miss You 12 2122

CD 1997. Zusaan Kali Fasteau/Noah Howard/Bobby Few, Expatriate Kin, CIMP 140 CD 2000. Bobby Few, Continental Jazz Express-Live at the 2000 Vision Festival, NYC, Boxholder 026 CD 2000. Bobby Few/Avram Fefer/Wilber Moris, Few and Far Between: Live at Tonic, Boxholder 029

CD 2002. Bobby Few, Let It Rain, BF01

CD 2004. Bobby Few/Avram Fefer, Kindred Spirits, Boxholder 048 CD 2004-Bobby Few, Lights and Shadows, Boxholder 054

CD 2004-05. Avram Fefer, Bobby Few, Heavenly Places, Boxholder 049CD 2007. Bobby Few/Sonny Simmons, True Wind, Hello World 12-13

Sideman

LP 1968. Marzette Watts Ensemble, Savoy 12193 (Bill Dixon)

CD 1968. Booker Ervin, The In Between, Blue Note 8 59379-2

LP 1969. Albert Ayler, Music Is the Healing Force of the Universe, Impulse! AS9191

LP 1969. Albert Ayler, The Last Album, Impulse! AS9208

LP 1969-70. Archie Shepp, Pitchin Can, America 6106

LP 1969. Frank Wright, One for John, BYG/Actuel 529 336

LP 1970. Noah Howard, Space Dimension, America 6108

LP 1970. Frank Wright, Uhuru Na Umoja, America 6104

LP 1970. Frank Wright, Church Number Nine, Calumet 3674

LP 1970. Archie Shepp, Coral Rock, America 6103

LP 1970. Alan Silva & Celestrial Communication Orchestra, Seasons, BYG/ Actuel 529.342/43/44

LP 1971. Hans Dulfer, El Saxafon, Ctfish 5C064-24515

LP 1972. Workshop Freie Musik, FMP R1/2/3

CD 1972-78. Frank Wright Quartet-Center of the World, Fractal 006 (=Center of the World en coleader, sorti sous le nom du Frank Wright Quartet)

CD 1972-78. Frank Wright Quartet-Last Polka in Nancy?, Fractal 007 (=Last Polka in Nancy?+un inédit de 1978, sorti sous le nom du Frank Wright Quartet) LP 1974. Frank Wright, Unity, ESP 4028

LP 1977. Joe Lee Wilson, Secrets From the Sun, Sun Records 113

CD 1977. Noah Howard, Red Star, feat. Kenny Clarke, Boxholder 014

LP 1979. Sunny Murray, Aigu-Grave, Marge 11

LP 1980. Noah Howard, Traffic, Frame 2005

LP 1980-81. Steve Lacy, Ballets, HatArt 1982-83

CD 1981. Steve Lacy, Songs, HatArt 6045

LP 1981. The 20th Anniversary Album, Jazzgalerie Nickelsdorf (Wright/Few/Gregg/Ali)

CD 1982. Steve Lacy, The Flame, Soul Note 1035

CD 1982. Steve Lacy, Clichés, HatOLOGY 536

CD 1983. Steve Lacy, Two Five & Six/Blinks, HatArt 6189

LP 1983. Steve Lacy, Prospectus, HatArt 2001

CD 1985. Steve Lacy, The Condor, Soul Note121135-2

LP 1985. Mike Ellis, What Else Is New?, Alfa 8016

DVD 1985. Steve Lacy Lift the Bandstand, Rhapsody Films 2869046 (sortie 2005)

CD 1986. Talib Kibwe, Odyssey, Madrigal 3033

CD 1986. Steve Lacy, The Gleam, Silkheart 102

LP 1987. Steve Lacy, Momentum, RCA-Novus 3021

CD 1988. Steve Lacy, The Door, RCA-Novus 3049-2

CD 1989. Steve Lacy, Anthem, RCA-Novus 3079

CD 1990. Steve Lacy, +16 Itinerary, HatArt 6079

CD 1991. Steve Lacy, Live at Sweet Basil, RCA-Novus 63128-2

CD 1992. Steve Lacy, Clangs, HatArt 6116

CD 1992. Steve Lacy, Associates, Felmay 1001

CD 1993. Steve Lacy, Vespers, Soul Note 121260-2

CD 1994. Steve Lacy, Findings, CMAP 003/004

CD 1994-95. Zusaan Kali Fasteau, Sensual Hearing, Flying Note 9005

CD 1995. David Murray, Flowers Around Cleveland, Bleu Regard 354221 (CT1951)

CD 1996. Noah Howard, In Concert, Cadence 1084

CD 1996. Noah Howard, Live at the Unity Temple, Ayler 001

CD 1997. Zusaan Kali Fasteau, Comraderie, Flying Note 9006

CD 1997. Steve Lacy, Associates, New Tone 7009

LP 2001. Art Konik feat. Bobby Few- Finger, Comet 025

CD 2001. Ricky Ford, Songs for My Mother, Jazz Friends Productions 006

CD 2002. Gilles Peterson, GP02, Trust the DJ 89027

CD 2008-09. Jacques Coursil, Trails of Tears, Sunnyside 3085

CD 2009. Undivided, The Passion, Multikulti Project 011

CD 2009. Undivided, Moves Between Clouds, Live in Warsaw, Multikulti Project 002

CD 2012. Jacques de Lignières Quartet featuring Bobby Few, Engrenage, Musea Records D

*

|

VIDEOGRAPHIE

par Hélène Sportis

• Chaîne YouTube de Bobby Few

1968. Bobby Few, Booker Ervin (ts,fl), Richard Williams (tp), Cevera Jeffries Jr. (b), Lenny McBrowne (dm), «Sweet Pea», «Largo», «Tyra», album Booker Ervin, The In Between (Blue Note), Studio Rudy Van Gelder, Englewood Cliffs, JN, 12 janvier

1969. Bobby Few, Albert Ayler (ts,voc), Henry Vestine (g),Stafford James/Bill Folwell (b), Muhammad Ali (dm), Mary Maria (voc), «Toiling», album Albert Ayler, The Last Album (Impulse), Studios Plaza Sound, New York, NY, 26 au 29 août

1970. Bobby Few, Frank Wright (ts), Noah Howard (as), Arthur Taylor (dm), «Grooving», album Frank Wright Quartet, Uhuru Na Umoja (label America Records), Paris

1973. Bobby Few, Alan Silva (b), Muhammad Ali (dm), album-titre «More or Less Few», «Simone», (label Center of the World), Paris, novembre

1979. Bobby Few, piano solo, album-titre «Continental Jazz Express» (Vogue), Studios Sidney Bechet, Villetaneuse (93), France, 12 mars

1979. Bobby Few, Richard Raux (ts), Alan Silva (b), Sunny Murray (dm), Pablo Sauvage (perc), «Tree Tops», album Aigu-Grave (label Marge), Studio Ramsès, Paris 5e

1982. Bobby Few, Steve Lacy (ss), Dennis Charles (dm), album Steve Lacy Feat. Bobby Few and Dennis Charles, The Flame (Soul Note), Studios Barigozzi, Milano, Italie, 18-19 Janvier

1986. Bobby Few, Kibwe (as,ss,fl,kalimba,perc), Sangoma Everett (dm,perc), Louis Petrucciani (b), «Blues From Jaly», «I Love Music», «2000 Seasons, Part 1, Part 2», album Talib Kibwe Odyssey, Egyptian Oasis, Studio Guimick, Yerres (91), France, 4 au 6 avril

1986. Bobby Few (p), Paris Reunion Band, Woody Shaw (tp), Nat Adderley (crt), Leo Wright (as), Joe Henderson (ts), Grachan Moncur III (tb), Jimmy Woode (b), Idris Muhammad (dm), JazzTage Leverkusen, RFA, «Rue Chaptal, The Old Country, The Man From Potter's Crossing, Polka Dots and Moonbeams, Hot Licks», archives TV, 2 novembre

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vu-mC7NyDL4

1996. Bobby Few et Steve Potts (s), «Spirits», Le Cercle de Minuit, France2, archives INA, 11 décembre

2000. Bobby Few, Archie Shepp (fl,p,voc), Maxwell Price (tp,flh,prod), Wayne Dockery (b), Stephen McCraven (dm), Carol Cass (voc), «Coming on the Hudson», album Tribute To The Great Thelonious Monk (label Santosha Arts), 26-27 octobre

2000. Bobby Few, Avram Fefer (ts,prod), Wilber Morris (b), «Nostalgia in Times Square», album Few And Far Between (Boxholder Records), Live at Tonic, New York, NY, 4 juin

2001. Bobby Few, Ricky Ford (ts), Jean-Michel Couchet (as), Frédéric Burgazzi (tb), Emmanuel Grimonprez (b), Philippe Soirat (dm), «Pie Crust», album Songs for My Mother (label Jazz Friends Productions), 3 mars

2002. Bobby Few (p,voc), Jon Handelsman (ts), Rasul Siddik (tp), Harry Swift/Raymond Doumbe (b), Bob Demeo/Jean-Claude Montredon/Noël McGhie (dm), album Let It Rain (autoproduit Bobby Few), Studio Cargo, Montreuil (93), France, janvier

2005. Bobby Few, Avram Fefer (s), «Orange Was the Color of Her Dress», «Heavenly Places», «Come Sunday», Burlington-Vermont Discover Jazz Festival

2008. Bobby Few, Sonny Simmons (s), Masa Kamaguchi (b), Live at the ZDB Gallery, Lisbonne, © Nuno Moita , 11 octobre

2008. Bobby Few (p,voc), Harry Swift (b), Benjamin Sanz (dm), Rasul Siddik (tp), «Orange Was the Color of her Dress», «Let it Rain», The Danger of Jazz in Art, Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris, 12 mars

2010. Bobby Few (p,voc), Ernest Dawkins (s), Harry Swift (b), Ichiro Onoe (dm), Sant'Anna Arresi Jazz Festival, Sardaigne-Italie

2011. Bobby Few, Harry Swift (b), Jon Handelsman (ts, bcl), Ichiro Onoe (dm),

«Beautiful Africa», Studio z’AvantGarde, Paris 6e, © video dolphy00, 15 mai

2013. Bobby Few, Harry Swift (b), Ichiro Onoe (dm), Centre tchèque de Paris, Paris-Prague jazz club, 24 mai

2013. Bobby Few, Henry Grimes, Galerie Zürcher-Paris, 22 octobre

2013. Bobby Few (pianocktail, voc, Bobby joue le rôle de l’antiquaire), Romain Duris, Audrey Tautou, «Sophisticated Lady», film L’Ecume des jours (Michel Gondry)

2014. Bobby Few (p,voc), Harry Swift (b), Ichiro Onoe (dm), La Nuit du Live

2015-2017. Bobby Few, Musical Hurricane, documentaire sur Bobby Few, de Nicolas Barachin, présentation à La Java, Paris 10e, 14 février (compte-rendu dans Jazz Hot)

2016. Bobby Few (p,voc), Harry Swift (b), Ichiro Onoe (dm), «Single Petal of a Rose», Sunside-Sunset, Paris

2018. Bobby Few, Benjamin Sanz (dm), Musique Re-Belles Jazz Libre #2 Festival, Montreuil (93), Théâtre Berthelot, France, 21 octobre

2018. Bobby Few solo (p,voc), «Music is the Healing Force of the Universe» (Albert Ayler 1969), De Ruimte Club, Amsterdam, 8 février

* |

Bobby Few Trio: Bobby Few (p), Andy McKay (b), Oliver Johnson (dm), Marseille, 25 octobre 1984 © Ellen Bertet

Bobby FEW

«Fatboy»

La communauté américaine de Paris a perdu l'un de ses membres les plus emblématiques. Bobby Few s'était installé dans la Capitale en 1969, année où beaucoup d'Américains choisirent la Ville Lumière mais aussi la ville populaire qui était alors encore un symbole de liberté et de révolution (1789 et 1848) mais aussi de révoltes (des Trois Glorieuses à Mai 68, en passant par la Commune). Les temps ont bien changé, Paris n’est plus ce qu'elle était. Reste la nostalgie d'une époque, d'un Paris populaire où les marges existaient et d'un parcours de cinquante ans qui n'a jamais été facile sur le plan économique pour les artistes de jazz en général mais avec des moments chaleureux et parfois une solidarité à l'ancienne. Les artistes, les amis de Bobby Few témoignent… YS

• Bobby Few (1935-2021): comme un torrent

Irène AEBI-LACY (voc, vln, cello)

Bobby était différent des autres musiciens du sextet de Steve Lacy. Il était toujours un peu à part. Il parlait en poète et jouait comme un dieu. Mais il ne lisait pas la musique et faisait tout à l’oreille. Ce qui était fantastique aussi. Son jeu était très lyrique. Il utilisait tout le piano. Je n’ai jamais vu un musicien comme lui. Il était entièrement lui-même. Ses solos étaient d’une beauté! Il lui arrivait d’être emporté par la musique, et pouvait jouer sans s’arrêter. Bobby était un homme très gai. Steve l’adorait. Il me disait qu’il l’avait attendu pendant dix ans. Musicalement, il le comprenait vraiment.

Bobby was different from the other musicians in Steve Lacy's Sextet. He was always a little apart. He spoke like a poet and played like a god. But he didn't read music and did everything by ear. Which was fantastic too. His playing was very lyrical. He used the whole piano. I've never seen a musician like him. He was entirely himself. His solos were so beautiful. He would get carried away by the music at times, and could play without stopping. Bobby was a very cheerful man. Steve loved him. He told me he had waited for him for ten years. Musically, he really understood him. John BETSCH (dm)

«Fatboy», as I called him because he was so skinny, was the most unique individual on the piano that I have ever encountered. He played like nobody else. I forgot how I met him… We became close friends when I joined Steve Lacy’s Sextet in 1989. One day, I got a call from Steve Potts that Oliver Johnson was indisposed. I was already subbing in the Quartet. So, the sextet, with Bobby and Irène Aebi, was the next level. In that band, Bobby was the colorist. He had an impressionistic approach to harmony, which made everything take off.

I knew everyone in the band quite well. When I moved to Paris, I met Jean-Jacques Avenel and started working with him. He was such a treat, musically and personally. Hooking up with him was part of the magic of my coming to France. Whenever I heard the Quartet or the Sextet, it was a very uplifting experience. To be a part of the Sextet with Bobby was just phenomenal. It was serious work, but they were like family. On the piano, Bobby was always very strong. His solos were challenging and fun. He was also a very funny individual.

«Fatboy», comme je l'appelais parce qu'il était si maigre, était le pianiste le plus original que j'aie jamais rencontré. Il jouait comme personne d'autre. J’ai oublié comment je l’ai rencontré. Nous sommes devenus des amis proches lorsque j’ai rejoint le Sextet de Steve Lacy en 1989. Un jour, j’ai reçu un appel de Steve Potts me disant qu’Oliver Johnson n’était pas disponible. Je le remplaçais déjà dans le Quartet de temps en temps. Ainsi, le Sextet, avec Bobby et Irène Aebi, était la prochaine étape. Dans cette formation, Bobby était le coloriste. Il avait une approche impressionniste de l'harmonie, ce qui faisait tout décoller.

Je connaissais assez bien tout le monde dans le groupe. Lorsque j'ai déménagé à Paris, j'ai rencontré Jean-Jacques Avenel, et j'ai commencé à travailler avec lui. C'était un vrai régal, musicalement et personnellement. Entrer en contact avec lui a rendu magique ma venue en France. Chaque fois que j'entendais le Quartet ou le Sextet, c'était une expérience très édifiante. Faire partie du Sextet avec Bobby était tout simplement phénoménal. C'était un travail sérieux, mais ils étaient comme une famille. Au piano, Bobby a toujours été très fort. Ses solos étaient stimulants et passionnants. Il avait aussi beaucoup d’humour.Dave BURRELL (p) I met Bobby Few in Paris, France, in 1969 through my friends, drummer Mohammad Ali and tenor saxophonist Frank Wright. Bobby was an intelligent artist who brought vivid color to his piano style. We quickly became friends. In the early 70’s, Mr. Few and I were supportive of each other, showing up at concerts. Bobby was honored at Baltimore, Maryland's Johns Hopkins University's symposium: 50th Anniversary Algiers/Paris BYG in November, 2019, with me and distinguished guests Jacques Coursil, Archie Shepp, David Murray, Andrew Cyrille and Grachan Moncur, III. He was a catalyst who brought sophistication to the French musicians' participation in the avant garde jazz phenomenon in Europe.

J'ai rencontré Bobby Few à Paris, en 1969 par l'intermédiaire de mes amis, le batteur Mohammad Ali et le saxophoniste ténor Frank Wright. Bobby était un artiste intelligent qui a apporté des couleurs vives à son style de piano. Nous sommes rapidement devenus amis. Au début des années 1970, M. Few et moi nous soutenions mutuellement, en assistant aux concerts de l’autre. Bobby a été honoré lors du symposium de l'Université Johns Hopkins de Baltimore, Maryland, pour le 50e anniversaire Alger-Paris BYG en novembre 2019, avec moi et des invités de marque, Jacques Coursil, Archie Shepp, David Murray, Andrew Cyrille et Grachan Moncur III. Il a été un catalyseur qui a apporté de la sophistication à la participation des musiciens français au phénomène du jazz d'avant-garde en Europe.

Kent CARTER (b)

I met Bobby in Paris in the early 70’s. We were both on the same scene, the free jazz scene. At that time, he played with Frank Wright, Alan Silva, Muhammad Ali and others while I played with Steve Lacy, etc. It was always a pleasure to be with him, a very warmhearted man, fun to hang out with.

We played together several times in different situations, projects with Steve Lacy etc. It was a long time ago. Last time I had the pleasure to play with him was at Jean-Jacques Avenel’s memorial concert. His playing overwhelmed me. He sounded like a symphony orchestra all by himself.

Great music power, very inventive, very beautiful musician.

Thank you, Bobby Few.

J'ai rencontré Bobby à Paris au début des années 1970. Nous étions tous les deux sur la même scène, la scène du free jazz. A cette époque, il jouait avec Frank Wright, Alan Silva, Muhammad Ali et d'autres pendant que je jouais avec Steve Lacy, etc. C'était toujours un plaisir d'être avec lui, un homme très chaleureux, agréable d’être en sa compagnie.

Nous avons joué plusieurs fois ensemble dans des situations différentes, dans des projets musicaux avec Steve Lacy, etc. C'était il y a longtemps. La dernière fois que j’ai eu le plaisir de jouer avec lui, c’était au concert commémoratif de Jean-Jacques Avenel. Son jeu m'a bouleversé. Il était un orchestre symphonique à lui tout seul.

Une grande puissance musicale, très inventive. Un musicien magnifique!

Merci, Bobby Few.

Raymond DOUMBE (eb)

A mon arrivée en France, j’ai mis de côté la musique pour étudier l’histoire à la fac. Au Cameroun, je jouais de la basse, mais pas en professionnel. J’étais à Tolbiac et j'allais souvent au Dunois, l’ancien, qui était situé rue Dunois, dans le XIIIe arrondissement de Paris. Un club que j’aimais beaucoup. En 1979 ou 1980, j’y ai vu Bobby Few pour la première fois. Il jouait avec le Celestrial Communications Orchestra d’Alan Silva. C’était un vrai personnage. Il était tout maigre, et avait une façon très personnelle de poser ses doigts sur le clavier du piano.

Dix ans plus tard, Chris Henderson m’a appelé pour jouer avec Bobby au Duc des Lombards, car Tom McKenzie repartait aux Etats-Unis. Entre temps, j’avais travaillé avec Jef Sicard, Dominique Gaumont, le premier guitariste français qui a joué avec Miles, Salif Keïta… J’ai senti que je ne faisais pas l’affaire. Ma culture était la musique binaire africaine, pas le jazz. Mais Bobby a dû voir quelque chose en moi qui lui a plu, peut-être ma couleur rythmique.

Beaucoup de gens ont l’image de Bobby en tant que musicien de free jazz. Il écrivait aussi des chansons pop, soul, bossa comme «Latin Quarter», des ballades ou même un thème comme «China» avec des ambiances très asiatiques. Bobby avait l’âme de la musique noire.

D’ailleurs, on a joué un mois dans un club de Dakar avec lui et Noel McGhie. Il se comportait comme s’il avait toujours été en Afrique. Je me demande si ce n’était pas la première fois que Bobby s’y rendait. Pour Noel, ça l’était. Il était très ému. Moi, je connaissais déjà cette ville.

Le club était situé dans le vieux Dakar, qui avait été le centre névralgique du Sénégal pendant la colonisation. C’était un club huppé de la ville. Il y avait du monde tous les soirs. Comme Bobby était quelqu’un de très abordable et que les Sénégalais sont très chaleureux avec les étrangers, tout s’est merveilleusement passé. On jouait des standards, des ballades, beaucoup de compositions. Bobby aimait bien jouer des blues. Les gens aimaient beaucoup sa «Whiskey Song». Bobby et Noel étant des Afros, on est allé visiter l’île de Gorée. Tout cela a été une aventure incroyable!

En dépit de son âge, Bobby était un grand enfant, dans sa façon d’être, dans son humour. Il pouvait aussi s’adapter à toutes les situations. Je ne l’ai jamais vu s’énerver ni avoir un mot méchant envers qui que ce soit. Je suis resté dix ans avec Bobby. Il m’a ouvert un horizon. Si je compose aujourd’hui, c’est grâce à lui. Il a été le tournant de ma carrière.

When I arrived in France, I put music aside to study history in college. In Cameroon, I played bass, but not professionally. I was in Tolbiac and often went to the Dunois, the old one, which was located rue Dunois, in the 13th arrondissement of Paris. I loved this club! In 1979 or 1980, I saw Bobby Few there for the first time. He was playing with Alan Silva’s Celestrial Communications Orchestra. He was a real character. He was very skinny, and had a very personal way of touching the piano.

Ten years later, Chris Henderson called me to play with Bobby at the Duc des Lombards, because Tom McKenzie was going back to the US. In the meantime, I had worked with Jef Sicard, Dominique Gaumont, the first French guitarist who played with Miles, Salif Keïta… I felt I wasn’t the right fit. My music culture was African binary music, not jazz. But Bobby must have seen something in me that he liked, maybe my rhythmic color.

A lot of people think of Bobby as a free jazz musician. He also wrote pop tunes, soul, bossa songs like «Latin Quarter,» ballads and even a theme like «China» with very Asian vibes. Bobby’s music came out of the black spirit.

In fact, we played for a month in a club in Dakar with him and Noel McGhie. It seemed as though he had always been in Africa. I wonder if this was Bobby's first time there. For Noel, it was. He was very moved. I already knew this city.

The club was located in the historic district of Dakar, which had been the center of Senegal during colonization. It was a posh club. There were people every night. As Bobby was a very approachable person and the Senegalese are very warm with foreigners, everything went beautifully. We played standards, ballads, a lot of original tunes. Bobby liked to play the blues. People loved his «Whiskey Song» very much. Bobby and Noel being Afro, we went to visit Gorée Island. All of this was an incredible adventure!

Despite his age, Bobby was a big kid, in his way of being, in his humor. He could also adapt to any situation. I never saw him get angry or have a mean word to anyone. I spent ten years with Bobby. He opened me up to new horizons. If I compose today, it's thanks to him. He was the turning point in my career.

Avram FEFER (as, ts, ss, bs, bcl, cl, fl) Bobby Few was a great friend, a wonderful musician, husband, father, grandfather and great-grandfather. He and his wife Simone were radiantly beautiful together and they were always incredibly warm and hospitable to me, providing a home away from home every time I was in Paris. As a musician, Bobby covered a lot of territory and was always ready to go anywhere the music demanded. He could play very soulful and bluesy, or be extremely introspective and melodic, with a very light touch, almost tip-toeing over the keys, or he could put his foot down on the sustain pedal and let rip, with vast harp-like harmonic waves washing over everyone for long stretches, seeming to summon the gods themselves! Bobby and I embraced the seemingly contradictory worlds of traditional and avant-garde aspects of the music and often combined both in our performances or in the studio. We might play one set of Duke Ellington and Monk, followed by a second set of free improvisations based on our own compositions. I was especially touched by the telepathically sensitive way he approached my piece «Heavenly Places» (dedicated to Oliver Johnson and Wilber Morris), treating the thematic material with deep reverence while creating a sonic palette during his solos that expanded the work into a deeply universal dimension. I was honored when he added this piece to his own solo and trio repertoire. We officially met in the late 1990’s, played some warm-up gigs at jazz clubs around Paris and then a year later we recorded a live trio album in New York with the late great bassist Wilber Morris. It was a magical gig and you can hear immediately how spiritually connected the two of them were as they joined forces on some otherworldly vocalizations on the album ( Few and Far Between ). We followed this over the next several years with two duo albums (Kindred Spirits and Heavenly Places) and a quartet album (Sanctuary) featuring Newman Taylor Baker and Hill Greene. We also toured parts of the United States and Europe several times during this period. Bobby was great fun to tour with, especially on long drives through the Midwest. He treated me –Jewish and 30 years his junior– with great love and respect and we joked that he was my «adopted Dad.» (It was still me who had to set down «the rules of the road» when we were on tour though!). He was a treasured connection to a long and gifted lineage of musicians, full of stories and anecdotes that I will always hold dear. As a human being he was charming and warm, friendly, curious, and nearly always approachable to friends and fans alike. We shared a child-like sense of playfulness and awe about the world around us and could easily pass an hour by a lake just goofing off, quacking at ducks and looking at reflections of clouds in the water. He had a sense of optimism and naïveté that was unusual amongst many older jazz musicians, especially those who had lived abroad for a long time… He almost never sounded bitter or angry, despite the inherent difficulties of being a Black American artist born in the 1930’s. Playing with Bobby Few and experiencing his connection with an audience was one of the highlights of my musical life so far. The hardest part about it was remembering to grab my horn and play along. I was always so mesmerized just listening to the man himself!!

Bobby Few était un grand ami, un merveilleux musicien, mari, père, grand-père et arrière-grand-père. Lui et sa femme Simone étaient d'une beauté radieuse ensemble. Ils étaient toujours incroyablement chaleureux et hospitaliers avec moi, m’offrant une deuxième maison chaque fois que j'étais à Paris. En tant que musicien, Bobby couvrait beaucoup de territoire et était toujours prêt à partir où la musique l’exigeait. Il pouvait jouer très émouvant et bluesy, ou être extrêmement introspectif et mélodique, avec une touche très légère, presque sur la pointe des pieds sur les touches. Il pouvait aussi poser le pied sur la pédale forte et se lâcher, créant de grandes vagues harmoniques, comme à la harpe, qui nous submergeaient pendant de longues périodes, et semblaient invoquer les dieux eux-mêmes! Bobby et moi embrassions les mondes apparemment contradictoires de la tradition et de l’avant-garde, souvent combinés dans nos performances. Nous pouvions jouer un set de Duke Ellington et Monk, suivi d'un deuxième set d'improvisations libres basées sur nos propres compositions. J'ai été particulièrement touché par la manière télépathiquement sensible dont il a abordé mon thème «Heavenly Places» (dédié à Oliver Johnson et Wilber Morris), traitant le matériau thématique avec une profonde révérence tout en créant une palette sonore pendant ses solos, ce qui le rendait profondément universel. J'ai été honoré lorsqu'il a ajouté ce thème à son propre répertoire solo et trio. Nous nous sommes rencontrés à la fin des années 1990, avons joué quelques concerts dans des clubs de jazz autour de Paris, puis un an plus tard, nous avons enregistré un album en trio live à New York avec le regretté grand bassiste Wilber Morris. C'était un concert magique. Vous pouvez entendre à quel point ils étaient spirituellement connectés lorsqu'ils unissaient leurs forces sur des vocalisations d'un autre monde sur l'album (Few and Far Between). Nous avons poursuivi les années suivantes avec deux albums en duo (Kindred Spirits et Heavenly Places) et un album en quartet (Sanctuary) avec Newman Taylor Baker et Hill Greene. Nous avons également fait plusieurs tournées aux États-Unis et en Europe pendant cette période. C’était très agréable de tourner avec Bobby, en particulier sur les longs trajets à travers le Midwest. Il me traitait –juif, de trente ans son cadet– avec beaucoup de respect. Nous plaisantions en disant qu'il était mon «père adoptif» (Mais c'était moi qui fixais les «règles du jeu» lorsque nous étions en tournée). Il était le lien précieux avec une longue et belle lignée de musiciens, pleine d'histoires qui me seront toujours chères. En tant qu'être humain, il était charmant et chaleureux, amical, curieux et presque toujours accessible aux amis et aux fans. Nous partagions un sentiment enfantin de crainte à propos du monde qui nous entoure, et nous pouvions facilement passer une heure au bord d'un lac à caresser des canards et à regarder les reflets des nuages dans l'eau. Il avait un sentiment d'optimisme et de naïveté qui était inhabituel chez de nombreux musiciens de jazz plus âgés, en particulier ceux qui avaient vécu à l'étranger pendant longtemps… Il n'avait presque jamais l'air amer ou en colère, malgré les difficultés inhérentes à être un artiste noir-américain né dans les années 1930. Jouer avec Bobby Few et faire l’experience du rapport qu’il avait avec le public a été l'un des moments forts de ma vie musicale. Le plus dur était de ne pas oublier de saisir mon saxophone et de jouer. L’entendre sur le piano était si fascinant!!

Bobby Few (p), Jean-Michel Couchet (as), Ricky Ford (ts), Frédéric Burgazzi (tb), Emmanuel Grimonprez (b), Philippe Soirat (dm) Festival Jazz sur son 31, 17 octobre 2001, Ramonville Saint-Agne © Alain Dupuy-Raufaste Ricky FORD (ts) The first time I met Bobby Few was at the Fête de l’Humanité in 1976. Gérard Terronès booked the festival. l was with Charles Mingus Quintet. We opened for Archie Shepp. John Betsch, then my neighbor on East 10th Street in New York, was with Archie. Backstage, after our set, we met Bobby along with Frank Wright. My first impression of Bobby was that he was full of joy and warmth. Mingus and Wright were having some philosophical discussion. And Charles was questioning whether it was useful for Frank to get on his knees when he was in the throes of a solo. Frank promised him that he would never get on his knees anymore when he played. We all laughed. Years later, I moved to Paris. Bobby collaborated on many projects of mine, such as my record Songs For My Mother. Bobby's playing was all encompassing. He had a very strong left hand. He could play in any style. We were also in Steve Lacy's Vespers tour. We shared a great moment in Washington, DC, during the 4th of July, enjoying the fireworks from my hotel window. Bobby's battle with Kirk Lightsey during the Toucy Jazz Festival in 2016, at the Galerie 14, is another great memory. Another year, Ran Blake was featured. He was transfixed when he heard Bobby. Years ago, I started the project to arrange music for big band that had never been arranged before. I did this with Steve Lacy. Bobby gave me the parts he had done with him. Now, I am doing this for Bobby’s music. Our love goes out to the Few Family.

La première fois que j’ai rencontré Bobby Few, c’était à la Fête de l’Humanité en 1976. Gérard Terronès s’occupait de la programmation. Je jouais dans le Charles Mingus Quintet. Nous avons ouvert pour Archie Shepp. John Betsch, alors mon voisin de East 10th Street à New York, était avec Archie. Dans les coulisses, après le concert, nous avons rencontré Bobby et Frank Wright. Ma première impression de Bobby était qu'il était très joyeux et chaleureux. Mingus et Wright s’étaient lancés dans une discussion philosophique. Et Charles demandait à Frank si c’était vraiment utile de se mettre à genoux quand il était plongé dans les affres d’un solo. Frank lui a promis de ne plus jamais le faire. Nous avons tous ri. Des années plus tard, j'ai déménagé à Paris. Bobby a collaboré à de nombreux projets, comme mon disque Songs For My Mother. Le jeu de Bobby était complet. Il avait une très solide main gauche. Il pouvait jouer dans n'importe quel style. Nous étions également dans la tournée de Vespers avec Steve Lacy. Nous avons partagé un beau moment à Washington, DC, le 4 juillet, en profitant des feux d'artifice depuis la fenêtre de mon hôtel. La battle de Bobby avec Kirk Lightsey lors du Toucy Jazz Festival en 2016, à la Galerie 14, est un autre grand souvenir. Lors d’une autre édition, il y avait Ran Blake qui a été ébloui par le jeu de Bobby. Il y a des années, j'ai commencé le projet d'arranger de la musique pour big band qui n'avait jamais été arrangée auparavant. J'ai fait ça avec Steve Lacy. Bobby m'avait donné les relevés que nous avions faits ensemble. Maintenant, je fais ça pour la musique de Bobby. Notre amour va à la famille Few.

Jack GREGG (b)

I met Bobby, Frank Wright and Muhammad Ali shortly after my arrival in Paris, at some time in 1977. It was probably at one of their gigs at the Riverbop, which was located rue Saint-André-des-Arts, in Odéon. Everybody played there.

At some point, I replaced Alan Silva in Frank’s Quartet. I did a lot of gigs with them off and on, in Holland, Switzerland… Man, they were all crazy, including Bobby! Bobby calmed down a lot when he got older. They were wild! They were gangsters! Their music was so intense, energetic and aggressive, not everybody in the audience could take it, but those who stayed just loved it.

I played more gigs with Bobby and his trio in the early 90’s and when I came back from Lebanon, in 2005. Before the first set at the Bimhuis, in Amsterdam, he told me, «Play water flowing. Think waterfalls tumbling and a cool stream in the mountains.» Nothing about chords or notes or time meters. He had the ability to paint sound pictures with his piano. Once, he looked at me and said one word, «Hurricane,» before launching an explosion on the piano. Bobby became a very sweet, highly spiritual person. Hear him sing «Let The Sun Shine In Your Heart» and «Girls Are Fun». Bobby is gone but he lives on in the hearts of those of us who played with him and were touched by his gentle spirit.

J'ai rencontré Bobby, Frank Wright et Muhammad Ali peu de temps après mon arrivée à Paris, durant l’année 1977. C'était probablement à l'un de leurs concerts au Riverbop, qui était situé rue Saint-André-des-Arts, à Odéon. Tout le monde y jouait.

A un certain moment, j’ai remplacé Alan Silva dans le Quartet de Frank. J'ai fait beaucoup de concerts avec eux de façon intermittente, en Hollande, en Suisse… Ils étaient tous dingues, y compris Bobby! Bobby s'est beaucoup calmé avec le temps. Ils étaient déchaînés! C'étaient des gangsters! Leur musique était si intense, énergique et agressive, que tout le monde dans le public ne pouvait pas la supporter, mais ceux qui restaient l'adoraient.

J'ai joué plus de concerts avec Bobby et son trio au début des années 1990 et, à mon retour du Liban, en 2005. Avant le premier set au Bimhuis, à Amsterdam, il m'a dit: «Joue l'eau qui coule. Pense à des chutes d'eau et à un ruisseau de montagne.» Pas un mot sur les accords, les notes ou le temps. Il avait la capacité de peindre des images sonores avec son piano. Une autre fois, il m'a regardé et a dit un seul mot: «Ouragan», avant de provoquer une tempête sur le piano. Bobby était un homme très gentil et hautement spirituel. Ecoutez-le chanter «Let the Sun Shine in Your Heart» et «Girls Are Fun». Bobby est parti, mais il vit dans le cœur de ceux d'entre nous qui ont joué avec lui et ont été touchés par son âme douce.Chris HENDERSON (dm) I met Bobby shortly after I arrived to Paris. It was in May 1980, at the Dreher, place du Châtelet. I was playing there with trumpeter Longineu Parsons. Then, we started working together in 1981-1982. At the time, I was practicing at Alan Silva’s school, IACP. One day, Bobby came down and heard me practicing. He asked me if he could practice with me. So, we started practicing together. He showed me some of his tunes and I started playing the drums to them. Then, he showed me his arrangements and the hits in certain parts of the melody and how that would change the song a little bit. That’s one of the biggest lessons I got from working with Bobby. He would take a song and arrange it a little bit differently than other people had played it. He taught me a lot about arranging. Since he was playing free on his tunes, my ears became attuned to that. I had previously worked, toured and recorded with Marion Brown at UMass Amherst. I learned a lot from him too. But Bobby really taught me how to change from one color to another. He would explain to me the different colors he would like to see. That was part of his arranging skills. From 1982 to 1988, we did a lot of work together with Alan Silva, Noah Howard, Frank Wright. Bobby got to draw more expressions out of me. He taught me how to express myself better. Our first combination was a duet when we were practicing together at IACP. Then we played in a trio, with Bobby, Alan Silva and I. Later, Bobby played solo at the Duc des Lombards. He asked me to play the snare drum. Back then, it was a very small place. I was playing underneath the staircase! At some point, Bobby suggested to the owner to build a stage, which he did. So, I was able to bring my snare drum, my cymbal and my hi hat. Then, he suggested to him to build a restaurant upstairs so that people could sit down and enjoy the music, which he did as well. Then, he suggested that he buy the jewelry shop next door. The club got bigger and bigger. I was able to bring a complete drum set. Now, I was sitting right next to Bobby. Bassist Tom McKenzie or Armistead Dailey joined us, sometimes singer Annette Lowman. Then, saxophonist Sulaiman Hakim was added as a fourth member. But I loved working with him as a duet. That was something special for me. I worked there with Bobby from 1985 to 1988. Then, one day, the owner said the group wouldn’t be playing there anymore. We couldn’t believe it. It wasn’t just a place where we went to play some jazz, it was a family house. Over the years, I played more with Bobby than anybody else. We were in harmony together. What made Bobby so interesting to play with is that he could play everything, whether it was his tune «China» which he sang to, his «Big Fat Mama» blues, Booker Ervin’s «The In-Between» in a more straight-ahead style or «Mister Kidnap Man», a John Lee Hooker style blues. No matter the styles, they always had that Bobby Few flavor to them. During my time with Bobby, I worked with Sun Ra off and on. Both of them could really play the blues! They understood 360 degrees of Black music. Actually, in 2017, Bobby played in the Arkestra in Paris. Knoel Scott told me they needed a piano player. The only person I knew that could do that was Bobby Few. The day of the concert, Bobby didn’t have a chance to rehearse with the band. They gave him sort of music sheets. So, he had to go with his feelings. To sit down in Sun Ra’s band and play the piano, that’s a heavy job. But Bobby fit right in. It was amazing what Bobby did that night.

J'ai rencontré Bobby peu de temps après mon arrivée à Paris. C'était en mai 1980, au Dreher, place du Châtelet. J'y jouais avec le trompettiste Longineu Parsons. Ensuite, nous avons commencé à travailler ensemble en 1981-1982. A l’époque, je m'exerçais à l’école d’Alan Silva, l’IACP. Un jour, Bobby est venu et m'a entendu travailler. Il m'a demandé s'il pouvait s’exercer avec moi. Alors, nous avons commencé à nous exercer ensemble. Il m'a montré certains de ses thèmes, et j'ai commencé à l’accompagner. Ensuite, il m'a montré ses arrangements et les hits dans certaines parties de la mélodie, et comment cela allait changer un peu le thème. C’est l’une des plus grandes leçons que j’ai tirées de mon travail avec Bobby. Il prenait un thème et l'arrangeait un peu différemment des autres personnes qui l'avaient joué. Il m'a beaucoup appris sur l’art d’arranger. Puisqu'il jouait librement sur ses thèmes, mon écoute s'est formée aux improvisations. Auparavant, j'avais travaillé, tourné et enregistré avec Marion Brown à UMass Amherst. J'ai aussi beaucoup appris de lui. Mais Bobby m'a vraiment appris comment passer d'une couleur à une autre. Il m'expliquait les différentes couleurs qu'il aimerait voir. Cela faisait partie de ses talents d’arrangeur. De 1982 à 1988, nous avons beaucoup travaillé avec Alan Silva, Noah Howard, Frank Wright. Bobby a pu tirer plus d'expressions de moi. Il m'a appris à mieux m'exprimer. Notre première collaboration était un duo lorsque nous nous exercions ensemble à l'IACP. Puis, nous avons joué en trio, avec Bobby, Alan Silva et moi. Plus tard, Bobby a joué en solo au Duc des Lombards. Il m'a demandé de jouer de la caisse claire. A l'époque, c'était un tout petit endroit. Je jouais sous l'escalier! A un moment, Bobby a suggéré au propriétaire de construire une scène, ce qu'il a fait. J'ai pu apporter ma caisse claire, ma cymbale et ma charleston. Ensuite, il lui a suggéré de construire un restaurant à l'étage pour que les gens puissent s'asseoir et profiter de la musique, ce qu'il a fait aussi. Puis, il lui a suggéré d'acheter la bijouterie voisine. Le club s’est agrandi. J'ai pu apporter tout mon kit de batterie. Maintenant, j'étais assis juste à côté de Bobby. Le contrebassiste Tom McKenzie ou Armistead Dailey nous ont rejoints, parfois la chanteuse Annette Lowman. Ensuite, le saxophoniste Sulaiman Hakim a été ajouté comme quatrième membre. Mais j'adorais travailler avec lui en duo. C'était quelque chose de fort pour moi. J'ai travaillé au Duc avec Bobby de 1985 à 1988. Puis, un jour, le propriétaire a dit que le groupe n’y jouerait plus. Nous ne pouvions pas y croire. Ce n’était pas seulement un endroit où nous allions jouer du jazz, c’était une maison familiale. Au fil des années, j'ai joué avec Bobby plus que n'importe qui d'autre. Nous étions en harmonie ensemble. Ce qui rendait Bobby si intéressant, c'est qu'il pouvait tout jouer, que ce soit son thème «China» sur lequel il chantait, son blues «Big Fat Mama», «The In-Between» de Booker Ervin dans un style plus straight-ahead ou «Mister Kidnap Man», un blues à la John Lee Hooker. Peu importe les styles, ils avaient toujours cette saveur Bobby Few. Pendant mon temps avec Bobby, je travaillais avec Sun Ra de façon intermittente. Tous deux pouvaient vraiment jouer le blues! Ils maîtrisaient les 360 degrés de la musique noire. En fait, en 2017, Bobby a joué dans l'Arkestra à Paris. Knoel Scott m'a dit qu'ils avaient besoin d'un pianiste. La seule personne que je connaissais capable de faire ça était Bobby Few. Le jour du concert, Bobby n’a pas pu répéter avec le groupe. Ils lui ont donné des sortes de partitions. Donc, il devait y aller au feeling. Intégrer le groupe de Sun Ra et jouer du piano, c’est difficile. Mais Bobby était comme un poisson dans l’eau. C'est incroyable ce qu’il a fait ce soir-là.

Stafford JAMES (b)

I am saddened by the passing of pianist Bobby Few. My sincere condolences to his family. With having met him in 1969 in New York just prior to our recordings with the legendary saxophonist, Albert Ayler. In my opinion, Bobby Few added a unique textural dimension to the music of the recording with his harmonic voicings and deft touch in tandem with a wonderful effervescence of personality. This made for a wonderful time to be had by all and the recording has survived the passage of time. I would also opinionate that Bobby Few knew that special path that he would pursue and one is indeed blessed who knows that path in life, and can maintain both the conceptual and mental fortitude necessary for that journey, as the road is both a long and arduous pursuit.

I am honored to have known and recorded with Bobby Few. May he forever rest in peace knowing that Music is indeed the healing force of the universe and his life was a testament to this.

Je suis attristé par le décès du pianiste Bobby Few. Mes sincères condoléances à sa famille. Je l'avais rencontré en 1969 à New York juste avant nos sessions d’enregistrements avec le saxophoniste légendaire Albert Ayler. A mon avis, Bobby Few a ajouté une texture unique à cette musique avec ses voicings, son toucher et sa personnalité effervescente. Nous avons tous passé un beau moment ensemble et le disque a survécu à l’épreuve du temps.

Je dirais aussi que Bobby connaissait le chemin qu’il allait suivre. Est béni celui qui le connaît et maintient la force conceptuelle et mentale nécessaire, car la route est longue et sinueuse.

Je suis honoré d'avoir connu et enregistré avec Bobby Few. Puisse-t-il reposer pour toujours en paix sachant que la Musique est en effet la force de guérison de l'univers et que sa vie en a été le témoignage.Alain JEAN-MARIE (p) J’ai connu Bobby Few dans les années 1970 quand il jouait avec Center of the World à l’American Center, boulevard Raspail. C’était un quartet fabuleux par la musique et par la joie de vivre qu’il dégageait. Je le voyais aussi au Dunois avec le Celestrial Communication Orchestra d’Alan Silva. Une fois, l’orchestre jouait. Bobby n’était pas là. A un moment, on a entendu le piano. Alan s'est retourné et a vu Bobby. Un immense sourire a éclairé son visage. Je l’ai vu aussi avec le saxophoniste Jo Maka et le percussionniste Cheikh Tidiane Fall. Son piano remplissait la musique, harmoniquement et rythmiquement, à tel point qu’on ne s’apercevait même pas qu’il manquait la contrebasse. Le voir jouer en piano solo, c’était très impressionnant. Je me souviens d’un concert au festival de jazz d’Essaouira. Il jouait la musique de Duke Ellington. Son jeu était très délicat. Quels que soient le tempo, le thème ou la formation, on entendait toujours le blues. Bobby était un homme très généreux et d’une grande humanité.

I met Bobby Few in the 70’s when he was playing with Center of the World at the American Center, on Boulevard Raspail. It was a fabulous quartet for the music and the joie de vivre it exuded. I also saw him at the Dunois with Alan Silva’s Celestrial Communication Orchestra. Once the orchestra was playing. Bobby wasn't there. At one point, we heard the piano. Alan turned around and saw Bobby. A huge smile lit his face. I also saw him with saxophonist Jo Maka and percussionist Cheikh Tidiane Fall. His piano filled the music, harmonically and rhythmically, so much that you didn't even notice the double bass was missing. Watching him play the piano solo was very impressive. I remember a concert at the Essaouira Jazz Festival. He was playing music by Duke Ellington. His piano playing was very delicate. Whatever the tempo, the song or the group, you always heard the blues. Bobby was a very good-hearted man and of great humanity.

George LEWIS (tb)

I was saddened to hear about the passing of Bobby Few. As a young person in the 70’s, discovering new music, I had already become a devotee of Bobby’s performances on the recordings with Noah Howard, Frank Wright, Muhammad Ali, and Alan Silva. It was amazing to actually come to Paris in 1982 and play with him in Steve Lacy’s ensembles, including the album Prospectus from 1983, which was my favorite among the work we did from that period. Wherever Bobby went, he brought with him tremendous, vitality, force, focus, and generosity with his encyclopedic musical knowledge.

J'ai été attristé d'apprendre le décès de Bobby Few. Le jeune que j’étais dans les années 1970, découvrant de nouvelles musiques, était déjà un adepte des performances de Bobby sur les disques avec Noah Howard, Frank Wright, Muhammad Ali et Alan Silva. C'était inouï de venir à Paris en 1982 et de jouer avec lui dans les formations de Steve Lacy, y compris sur l'album Prospectus de 1983. Mon préféré de cette époque. Où que Bobby aille, il apportait avec lui une formidable vitalité, force, concentration et générosité grâce à ses connaissances musicales encyclopédiques.

Noel McGHIE (dm)

The first time I met Bobby Few was in 1958, in Kingston, Jamaica. I was 14 years old. Bobby was playing with the singer Brook Benton, who was a big star at the time. I did not have any money for the show at the Tropical Theater, so I went to the soundcheck… The next time I saw Bobby was in 1970 at Le Chat qui Pêche, when I moved to Paris. He was there with Frank Wright, Noah Howard, Muhammad Ali and Bob Reid. We became instant friends. We shared an apartment in Asnières-sur-Seine with Noah Howard. We would practice together. Then I started working with Noah. That’s another story…

Bobby was one of the few people that liked the way I played. I was a real free jazz drummer. He recruited me in 1988 after Chris Henderson left. At the time, Bobby was working at the Duc des Lombards. He basically created this club. When the club was a just a hole in the wall, he was playing solo there and had a quartet, with Sulaiman Hakim, Raymond Doumbé, and Chris Henderson. Then, the Duc expanded and he couldn’t get a gig there anymore!

Bobby is a big part of my life. I worked with him for 20 years. We toured all over. People loved him. When we were in Dakar, we played on TV. The next day, Bobby was a super star! But he was not just a free jazz player. He could also play bebop, African type tunes, and wrote a lot of songs. He was such a unique person, with a very personal approach to life. Bobby was my beacon.

La première fois que j'ai rencontré Bobby Few, c'était en 1958, à Kingston, en Jamaïque. J'avais 14 ans. Bobby jouait avec le chanteur Brook Benton qui était une grande vedette à l'époque. Je n'avais pas d'argent pour le spectacle au Tropical Theater, alors j’ai assisté à la balance… La fois suivante que j'ai vu Bobby, c'était en 1970 au Chat qui Pêche, quand j'ai déménagé à Paris. Il jouait avec Frank Wright, Noah Howard, Muhammad Ali et Bob Reid. Entre nous, une véritable amitié est née. Nous avons partagé un appartement à Asnières-sur-Seine avec Noah Howard. Nous nous exercions ensemble. Puis, j'ai commencé à travailler avec Noah. C’est une autre histoire…

Bobby était l'un des rares musiciens à apprécier ma façon de jouer. J'étais un vrai batteur de free jazz. Il m'a recruté en 1988 après le départ de Chris Henderson. A l'époque, Bobby travaillait au Duc des Lombards. C’est lui qui a essentiellement lancé ce club. Quand le club n'était qu'un bouge, il y jouait en solo et avec son quartet, Sulaiman Hakim, Raymond Doumbé et Chris Henderson. Puis, le Duc s'est agrandi, et Bobby n’y trouvait plus de gigs!

Bobby fait partie de ma vie. J'ai travaillé avec lui pendant vingt ans. Nous avons tourné partout. Les gens l'aimaient. Quand nous étions à Dakar, nous avions joué à la télévision. Le lendemain, Bobby était une vraie star! Mais il n'était pas seulement un joueur de free jazz. Il pouvait aussi jouer du bebop, des airs africains, et a écrit beaucoup de chansons. C'était un homme si unique, avec une approche très personnelle de la vie. Bobby était mon phare.

Famoudou Don MOYE (perc)

In 1969, I was playing in Rome with Steve Lacy. One day, he said, «I want to get out of here. This place is killing me! You want to go to Paris?» I said, «Hell, yeah!» So, we packed up and moved to Paris. The first day we got there I met Bobby Few, Muhammad Ali, Frank Wright, Arthur Taylor and Johnny Griffin. They were all sitting at a café on the corner of rue Saint-André-des-Arts and rue de Buci. At that time, many musicians were staying at Hôtel de Buci. Bobby, Muhammad and Frank were all staying there. That’s where we went. There were many jazz clubs. We used to go all the time to Le Caméléon and the Riverbop. They were like my big brothers. I joined the Art Ensemble of Chicago shortly after.

Bobby was always helpful and encouraging. He gave me tips about the scene in Paris. I would see him all the time at the American Center, on boulevard Raspail. I played there with him, Dave Burrell, Oliver Johnson, Jerome Cooper, and all the individuals of the Art Ensemble.