Lenny Popkin

Feelin’ the music

Lenny Popkin (see in Jazz Hot n°619, 2005) is a humanist.

Born on May 30th, 1941 in New York, the saxophonist’s awareness to jazz was raised by the artists Louis Armstrong and Earl Bostic when he was in his teens. Although he was disappointed by his studies at Lenox School of Jazz in 1959 –the same year as Ran Blake, Steve Kuhn, Gary McFarland, Ornette Coleman– and at Brandeis University, his years of apprenticeship were enlightened by being around other jazz musicians.

Lenny Popkin’s name is inextricably tied in with Lennie Tristano’s, with whom he shared the same desire for music, the love of improvisation, the attentive listening to records and this integrity in the precise knowledge of the history of jazz music.

Guided by feeling, as a source of knowledge, Popkin works on his improvisation like a craftsman.

With fifteen records as a leader, among which five with pianist Connie Crothers and two produced by Arnaud Boubet, founder of Paris Jazz Corner (New York Moment in 2005 and Time Set in 2012), Lenny Popkin continues to deepen a pure aesthetic, with his playing seemingly simple and natural, as a watercolor or a drawing made by a great master.

In one of his poems, Swiss poet Philippe Jaccottet wrote : « Let self-effacement be my way of blazing ». Who better than Lenny Popkin to work under this motto? The music of the saxophonist with a strong personality and intense musical presence is the one of the elusive, of pure improvisation, this creative instant that generates beauty between its mysterious intervals.

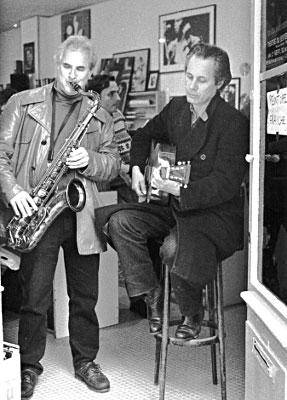

Living in Paris with his wife, drummer Carol Tristano, for the past eight years, the saxophonist has been playing with his trio, composed of his wife and French bass player Gilles Naturel. Popkin has also played with other great French musicians, Philippe Soirat, Jean-Philippe Viret, Alain Jean-Marie and Dominique Cravic.

Interview by Mathieu Perez

Photos Jos Knaepen, Mathieu Perez and Bernard Savoïa Ailloud

© Jazz Hot #668, Summer 2014

Jazz Hot: What is your first memory of jazz?

Lenny Popkin: One awakening for me was when I was 13 and I heard a Louis Armstrong record, which was something he made in the ‘30s. I identified with the feeling of what he was doing – and the music also – the line he was creating, the feeling of his band at the time. I didn’t know what to do about it exactly, but I just remember being drawn to it and listening to it over and over again and feeling some very strong identification with him. I felt that there was something nurturing in his feeling. That began to change things for me – although at the time I was playing violin and I didn’t know what I wanted to do. Music was drawing me in different ways.

When did you switch to the saxophone?

I was in Switzerland for a summer when I was 15. On a jukebox, I heard an Earl Bostic record. It was this tune "Flamingo” which was a hit at the time. For some reason, I was drawn to the alto saxophone because of him. I even learned to growl like he would do. Then it just evolved. I heard Paul Desmond. He moved me. I was going to a prep school one summer in Massachusetts. They had only one jazz record in the library, which was a record released under the name of Lee Konitz. Lennie Tristano was on it as well as Warne Marsh and Sal Mosca. I listened to it over and over. It drove everyone crazy! (Laughs) That experience opened my eyes to different possibilities. I also had a record that had Charlie Parker on one side and Stan Getz on the other. I listened a lot to that also.

Why did you want to go and study at Lenox School of Jazz in 1959?

I heard about it because Lee Konitz had taught there one year. I thought there was some kind of connection. That was also an awakening. Their conception of what jazz was didn’t match mine. For me, the improvising part has always moved me the most. I appreciate a good arrangement but the improvising part is what turns me around. It’s still the part that I respond to the most. But I found that it was what they were the least interested in! They would talk about Jelly Roll Morton, his arrangements and the form of his compositions, etc. I wasn’t that interested in that.

What group did you play in?

My group was fronted by Jimmy Giuffre. At that time, he was in a phase where he was turned around by Sonny Rollins. So he was trying to play that way. To me, his writing seemed a little self-conscious. Herb Pomeroy led the big band. I really enjoyed that. Kenny Dorham was teaching there too. I wasn’t in his group but I liked it. I also enjoyed being around the students. I had envisioned jam sessions where everyone would be improvising all night long but it didn’t happen that way. People were antagonistic to Lee Konitz and Lennie Tristano. Bird, they knew something about, but he wasn’t a focus of discussion. They were focusing mainly on Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk …

How did you respond to George Russell’s teaching?

Well, same thing. I felt he was self-consciously trying to inject things into his music to get a certain sound. He was a composer/arranger – not an instrumentalist.

We all had to buy his book called The Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization. To me, the harmony that Charlie Parker and Lennie Tristano had come up with opened up a huge world already, but Bird wasn’t being talked about and Lennie’s music hit a stonewall of negativity.

Then did you feel this was not the right place for you?

I wanted to be around that scene but I couldn’t share anything of what I felt with anybody except for some people that were around. Milt Jackson was there briefly. We had a nice conversation. I met Bill Russo. Later on, I studied with him for a summer. His work with Stan Kenton is really great. I also met Joe Morello.

What was the vibe like?

You felt it was the launching of Ornette Coleman’s career. His playing was a bluesy kind of thing and he would throw in what I would call "sounds”. He threw in the "sounds” when the changes became complicated. (Laughs) I certainly did not feel I was listening to a saxophone player on the level of a Charlie Parker. And later, I got angry when he was attributed with the innovation of free playing because it had already been done by Lennie and his band ten years earlier and publicly, not only on records. I have documentation on that. There are several sources. Pianist Ronnie Ball wrote an article in an English magazine, Melody Maker, about it back in 1951. He described what went on when Lennie’s band was playing in Birdland and how it felt to be there when they played free. The audience loved it. He didn’t announce what he was going to play otherwise the audience would have frozen. He just played it.

When did you hear about Lennie Tristano?

My first awareness was from the Prestige LP with Lennie’s Quintet. They all played great on it but Lennie’s playing was spectacular. Today in a list of great pianists, he almost is never mentioned. Even when we go back to his early recordings in 1945, 1946, he’s a staggering pianist. How could you be dazzled by Art Tatum and be unaware of Lennie Tristano, who did what Art did, only improvising? His music is truly original.

Were you interested in Lennie Tristano’s free stuff?

I appreciated it but the free stuff didn’t turn me around. I was more interested in improvising over the harmonies of tunes. I could identify with that more. Also I never heard him do that (play free) live. That’s part of it. I loved the steady flow of the rhythm section. There is a beautiful jazz feeling in those free pieces. Today I listen to them with a different ear and appreciate them more. I love Lennie’s solo piano line in the beginning of "Intuition” – and I think the harmonies they spontaneously created are beautiful and unique.

When did you see Lennie Tristano play live for the first time?

When I first heard Lennie’s band, it was in 1959 at the Half Note. Not only could you hear the harmonic flow, but also he would play harmonies on top of harmonies and rhythms on top of rhythms. It was all flowing, natural and improvised. That’s the first time that I heard live what I wanted to hear.

What do you remember of the atmosphere of the gig?

It was serious but not in a tight sense. They were playing music for real. The response from the audience was great. It was great being there. It was electrifying. It was pure music and pure jazz. They would start at 10 pm and play until 4 am. They would be there for two weeks and I’d go there every night. By the end of the night, my friends and I would leave kind of singing along with what we had just heard. The music stayed with you. It matches the description I have heard about what people felt hearing Bird on 52nd Street. It was that kind of excitement.

Did you feel a connection with him immediately?

I would talk with him in between sets. One thing I will never forget is when I asked him how he felt about Monk, Brubeck, etc., he answered me very seriously. I was only 17 or 18. He didn’t talk down to me or like he was talking to a kid. He expressed exactly how he felt. No mincing of words. At that point, there was an immediate connection.

Why did you go and study at Brandeis University?

I went to Brandeis partly because I had heard there had been a jazz festival there. Tristano, Mingus, etc., had played there. But when I got there, they weren’t the least bit interested in jazz! (Laughs) In fact, they discouraged it. During orientation week, I was playing in the music building, improvising. There was a knock on the door by Irving Fine, who was known at the time for being identified with Third Stream. He was teaching there. He said that jazz wasn't allowed in the music building. (Laughs) That was my introduction to Brandeis… I had a split personality. I took courses in composition, music history, etc., but I was playing jazz. Then I began to study with Lennie. I would commute from Boston every week. And I maintained contact with him for the next twenty years.

Did you study with Lennie Tristano after studying with Lee Konitz?

I had studied briefly with Warne first. I remember things we discussed. Warne’s playing at that time also changed my life because of the beauty of his sound and the way it filled the club. The music he was producing was very moving to me. After that, I studied with Lee for about a year.

How do you reflect on their teaching?

Some of it had to do with their individual personalities. Lennie, his way of teaching was all there. And then of course it’s just who he is as a person. He was very magnetic, spontaneous, brilliant – all these things. Most of all – he was fun to be around. It was always enjoyable and exciting to be around there. He had a waiting room. Sometimes there would be three or four other people waiting. The feeling was always happy. Everybody was excited. When you left, you were sailing. It was a beautiful experience. Without exception. Every time.

In those days, where would you go to play music?

I had a few colleagues. I met Matthew Notkins, an alto player, at the Half Note. We followed a similar journey. We played together. Like Lennie said, when you have another person, it’s a session. The big turning point was Sal Mosca. He was living in Mount Vernon and had his own studio. Generously he would let us come up and play sessions.

I think it was on Thursdays. You never knew who would show up. For a while, there was drummer Roger Mancuso, bass player Lou Stelluti. Sal would sometimes play a tune but mostly sat in an adjoining room listening. It gave us something to look forward to every week. Later on, Sal and I played duo sessions – often twice a week. Also, Lennie invited me to sit in with his band at the Half Note while I was still playing alto. Later, in 1968, I played a gig with him as the tenor player in his quartet.

Did you have a chance to play with and/or befriend any musicians of an earlier era?

I met Roy Eldridge much later and we developed a friendship. I got to hear him play live. His personality was as intact as ever. And so was his music. One of his performances was recorded for a TV pilot called "After Hours. You see him walk into a club and everybody lights up. That’s the way he was and I did experience that quality. He was also very supportive. He came to a concert I did in 1979 that was recorded and has now been released on Candid. I played "Body and Soul” and dedicated it to him. I quoted from one of his choruses.

Which musicians from that era do you look up to?

From that era Lester Young, Roy Eldridge, Charlie Christian, Billie Holiday and Kenny Clarke. These are the people who changed the world. Those are the people I have been most influenced by. Anywhere on the instrument, Lester was at home. They don’t talk about his playing in the lower register. He played the greatest low b-flat on the tenor. It’s hard just to hit it! On "Easy Does It” with Count Basie, he hits a low b-flat and it’s beautifully expressive. To hit a note like that with a full beautiful sound is very difficult. One reason I’m mentioning this is because the standards of instrumental performance have seriously diminished since that era. Even for people who, for me, are not the top top top, but people like Johnny Guarnieri – he could play the hell out of the piano. Fats Waller – also for me, not one of my deepest sources of inspiration, but it’s dazzling the way he can play the piano. There are exceptions, but I rarely hear that level of achievement. Partly because the people who set the standards are, generally speaking, not being talked about that much. For example, Thelonious Monk, to me, is an indifferent piano player. His method of improvising is frequently to play the head melody over and over. I'm not saying anybody can’t enjoy that, but to put him out there as one of the great stars of jazz is something that I’ve never been able to identify with - compared to Bud Powell who is relatively unspoken about. Everybody is influenced by Bud Powell. Nobody is influenced by Thelonious Monk – maybe five or six people. They might play, "’Round Midnight”, or "Evidence”, but then, when it comes to the improvising, it’s coming from Bud Powell. People don’t talk about Bud Powell. The only person that talked about Bud Powell very seriously was Lennie Tristano. And he did many times. He did a whole radio broadcast on Bud Powell and drew attention to One Night in Birdland featuring Bird, Bud Powell and Fats Navarro. And, I would say a contemporary thing that bugs me is what I thought I witnessed with respect to Freddie Hubbard. He is the trumpet player to emerge from the 1960s. I feel a connection with him. I learned a lot from him and I love the way he played, particularly when he played straight-ahead. But he wasn’t talked about even then. If you read liner notes, they don’t say you’re about to hear something that’s going to knock your socks off. He didn’t receive the kind of attention Wynton Marsalis received. Wynton is nowhere near Freddie Hubbard in my opinion. Nobody is. I would also say that many of the people associated with Lennie, have been marginalized. I’m thinking of Connie Crothers and Kazzrie Jaxen, formerly Liz Gorrill. These are great pianists. They are contributors to the art form with very original voices.

Why do you think these musicians are still not being talked about?

I have my theories. People turned against jazz. I think there are many reasons for it. One of the reasons is, I believe, because it was the music, which was the first integrated music. Black and White together. And that went way back from the beginning. Louis playing "When You’re Smiling”. I think that was part of it. Because, at a certain point, Black and White were made to separate. But there’s another thing too. There’s something associated with jazz, which Black people also turned against. Because it became associated with, for example, tap dancing. And tap dancing took on a negative connotation – as if you were "shufflin’” or "jiving” – something like that. But actually, it is a profound art form. I think of Jimmy Slyde. He was a jazz tap dancer. He improvised. For a while, Barry Harris had a little place in Manhattan. On one Sunday afternoon, he was playing with a trio and Jimmy Slyde was tap dancing. It was magic. I’ll never forget that. Bojangles is great but it’s more technical and less improvised, which is another reason why things got turned around. People turned against improvising. If I go to a club, more often than not at least half of the tune is taken up with the arrangement, then there’s a little improvising and more arrangement. Sometimes for me it’s difficult to sit through the arrangements even though it’s musical and the person doing it is serious. I’m there to hear the improvising part. The reason why the improvising part is so significant to me is that it’s the part where the person is expressing himself live right in front of you. The great ones are expressing something of the essence of their personalities. I don’t mean what they are thinking about. There’s something about the essence of their being that comes out when a great improviser improvises. And you can hear it in every single note. So people turned against that. There’s a reason for that too. It is the most difficult thing to do. It’s easier to go out if you have something prepared. You know you have stuff you can do. But if you’re really serious about improvising, you do all your preparation before but you know that when it’s time to play you don’t know what’s going to happen. Another reason, and this may even be more responsible, is that there was never any money to be made in jazz. Stardom was not an option. So people resort to hyphenated jazz – jazz-rock, jazz-fusion, smooth-jazz and the like – the dilution of jazz by incorporating it into forms that make it easier to sell and package – with the attendant profits that flow from that sort of commercialization. Playing this kind of commercially viable music does not require the kind of technical proficiency required to improvise.

Did you feel there is a difference in the reception of jazz in Europe?

It depends. Sometimes I feel that people are influenced by what the American commercial interests think. Many jazz media take their cue from what America puts out there.

Since you have been living in Paris, have you met musicians whom you have enjoyed playing with?

Yes. I’ve had the pleasure of playing with many great and beautiful musicians. Gilles Naturel, Philippe Soirat, Jean-Philippe Viret, Alain Jean-Marie, Dominic Cravic. They are people for whom every note is important. I’d like to see the media focus on them. I feel that there is a real community of musicians here – and I’m happy to be part of it.

Is playing in Europe different?

It’s hard to make a generalization. In each crowd you can feel the people who are really listening. These are the people you’re playing for. Someone asked Lester Young a similar question and he said: "If a person like you, they like you, and if they don’t, they don’t like you. That’s all.” (Laughs)

You have been living in Paris for eight years. How do you feel in New York as opposed to Paris?

Personally I feel more relaxed here. New York is more in the grip of something that is

kind of an antagonism, a racial antagonism. If you’re going to define jazz as Black music, it’s an accepted term – they use it here too – "Musique noire”, but I don’t like that. Even recently, for example, I’ve seen B.B. King and Marvin Gaye referred to as jazz musicians. And this is based on the fact that they are perceived as Black. It can’t possibly be based on the fact that they are actually playing jazz. I know the way people were treated. If you’re treated as a Black person in America, that’s a particular way that society is treating you. But if I’m listening to a Roy Eldridge record, I don’t feel I’m listening to "Black music”. I’m listening to Roy Eldridge’s personal dimension. If you’re talking about ethnic stuff, then it’s worth considering that Charlie Parker was part Choctaw. I believe that Max Roach was part Cherokee. Oscar Pettiford, who was the founder of the modern jazz bass, was also part Choctaw. Nobody speaks of the influence of the Native Americans. So, it’s all a bunch of bullshit to me. All that kind of stuff separated Black from White, not from the people who are real, but in a commercial sense. To me, that is racist. I don’t want to hear Bird referred to that way. I’m not talking about how he experienced racism in America. I’m talking about him as a musician and talking about his music. Lennie Tristano made this point in an interview a long time ago: if Bird had been born in China, he would have been a great musician but he would not have played what became known as bop. He would have played something else. A lot of it has to do with the musical environment that these musicians came up in. I never experienced it directly but I can feel it when I listen to their music or read their stories. I can feel the joy that was being expressed, the vitality, the reality of the music.

Can you describe your personal preparation?

It’s a lifelong process. I listen a lot to people who move me. I get as close to that as possible. Lennie would have you sing with it. First, you have to listen to the music a lot. Then sing with it. That’s a way to experience it without doing anything technical. Then you learn to sing it away from the record. Now you’re experiencing it just coming from you. Then you would visualize it on your horn and see how it would fit. Then you play it on the horn. You can play with the record or away from it. It’s a way rather than a method. This way you’re dealing with the whole, not with notes or something written out. You’re dealing with the feeling. Throughout my life, I’ve tried to feel more and more what the people who move me are doing. I’m also very interested in thinking about what they did, how they played certain notes, the way they changed a passage, the way they placed a note. I love thinking about that. It’s fascinating to me. Ultimately my preparation has to do with deepening my feeling. You also have to get physically loose. If you’re tight, it’s very difficult to let your music flow from you. The other thing is learning your instrument the best you can, inside out and feel comfortable in all of the keys. Sometimes I’ll play a solo that I like in all the keys. That’s been my lifelong process. Every time I listen to the people whose music I love, I experience the same thrill only now I can experience it deeper. That’s my personal preparation. If I have the opportunity to play with musicians that enjoy playing with me too, like Gilles Naturel and Carol Tristano, we play for the pleasure of playing. They’re on my side and I’m on theirs. We're playing together.

What did you retain from Lennie Tristano's teaching to help build your own way of preparation and develop your own voice?

It would be hard for me to detach anything that I do from something I learned from Lennie because we talked about everything. I would go to study with him once a week. But, if anything occurred to me, I could call him up. Music was his passion. He loved to talk about jazz. He loved to talk about it with someone who was passionate about it. I was profoundly moved and influenced by where he was with jazz. I do feel that I’m playing in a way that is different than anybody. You don’t try to be different. At least I didn’t. I tried to be influenced by the people that moved me. Louis Armstrong was influenced by King Oliver, Lester Young by Frankie Trumbauer, Roy Eldridge by Red Nichols and Louis Armstrong and Bird by Lester Young. They were moved and inspired by others. It’s an evolution based on feeling, not material.

Do you use this way of preparation with your students?

Yes. I suggest things for them to sing with, and ways to learn their instrument in a way that will allow them to improvise. Each person is different. Everyone is their own universe. What you want to do is to get them in touch with that and help them express it. It’s amazing to hear it. Sometimes somebody will come up with something that they could not have possibly thought of because it comes from some place else within them. It’s not a conscious thing. It comes from your feeling.

Are you as comfortable playing in the studio as you are playing live?

They both have their place. They feel different. If you’re playing for an audience, you can feel the audience even if it’s one or two people. You feel it and it influences you in a way that is hard to define. Playing for a live audience has one feeling. In the Time Set album, which is a studio recording, there’s only Carol, Gilles and me. It has a particular feeling. A particular focus. They are different experiences and I enjoy them both.

Today you work with Carol Tristano and Gilles Naturel.

I have had the opportunity to play with Gilles and Carol for over 10 years – so we have developed a genuine rapport. Actually, we had it the first time we played together many years ago at the "7 Lézards”. So it has only deepened over time. These are two special people. Gilles is a great bass player. I’m always moved and astonished at his mastery of the instrument. He is responsive and giving. He is a great soloist, musician and person. He has also written some beautiful songs, and I love playing them with our trio. Carol is a great drummer. She has a beautiful and original sound. And she has an original and swinging time feeling. She has the amazing ability to create a joyful ambiance, coming from her strong jazz feeling. She also is a great soloist, musician and person. Together with Gilles, they are a dream rhythm section.

Concert

Sunset-Sunside, Paris, July, 8

Discography

Leader-coleader Leader-coleader

CD 1959. The Lenox Jazz School Concert-August 29, 1959, FreeFactory 064

LP 1979. Falling Free, Choice 1027

LP 1979. Lennie Tristano Memorial Concert, Jazz Records 3

LP 1984. True Fun, Jazz Records 7 (avec Liz Gorrill)

LP 1988. Love Energy, New Artists 1005 (avec Connie Crothers)

CD 1989. New York Night, New Artists 1008 (avec Connie Crothers)

CD 1989. In Motion, New Artists 1013 (avec Connie Crothers)

CD 1993. Jazz Spring, New Artists 1017 (avec Connie Crothers)

CD 1997. Session, New Artists 1027 (avec Connie Crothers)

CD 1997. Lenny Popkin, LifeLine Records 101

CD 2004. New York Moment, LifeLine/Paris Jazz Corner Productions 982 941-9

CD 2007. Belleville, Cristal Records 0714 (avec Gilles Naturel)

CD 2009. Live at Inntöne Festival, PAO Records 11160

CD 2010. 317 East 32nd, Candid Records 71027

CD 2012. Time Set, Paris Jazz Corner Productions/LifeLine 103

Vidéos

Lenny Popkin Trio au Duc des Lombards, Gilles Naturel (b), Carol Tristano (dm)

Lenny Popkin Trio Live at Brucknerhaus Linz, Mar 1 2011, Gilles Naturel (b), Carol Tristano (dm)

Lenny Popkin Trio Live at Brucknerhaus Linz, Mar 1 2011, Gilles Naturel (b), Carol Tristano (dm)

*

|

|