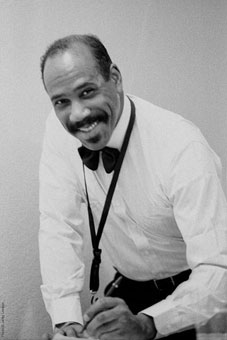

Sonny Fortune

|

September 22, 2013

|

|

Coltrane Legacy

|

|

© Jazz Hot n°665, autumn 2013

|

Sonny Fortune is loyal in friendhship. Born in Philadephia on May 19th, 1939, he started to play the saxophone at 18. As his interest was sparked by jazz, he dedicated himself to music and became a sought-after sideman for his powerful sound and soulful playing, whether it be on alto, tenor, soprano saxophone or alto flute. His career highlights include work with Elvin Jones (1967), Mongo Santamaria (1968-1970), McCoy Tyner (1971-1973), Buddy Rich (1974) and Miles Davis (1974-1975) and many others. Each one of his experiences have shaped him while expanding his personal style. In 1974, still working with Davis, Sonny Fortune recorded his second album as leader, Long Before Our Mothers Cried. Since then, he’s released over two dozen albums.

A demanding musician, committed to music and the pursuit of its authenticity, Sonny Fortune’s musical power relies on his personal style and what lies beneath its surface, which goes back to John Coltrane. In addition to his music, Sonny Fortune defends his values and promotes his conception of jazz and state of mind. His bonding with Elvin Jones, his friendship with McCoy Tyner and his encounters with musicians who shared their musical sensitivity deepened his relationship with Coltrane. In 2000, it lead to the album In the Spirit of John Coltrane. Each note expresses his own story and musical creativity as well as the history of jazz and the understanding of music.

Interview by Mathieu Perez

Discography by Guy Reynard

Jazz Hot: Which part of Philadelphia did your grow up in?

Sonny Fortune: Philly had sections. There was the North Philly section, the South Philly section, the East section, the West section, and there was the Germantown section. North Philly and Germantown were relatively close. Out of that location you got Reggie Workman, Lee Morgan, Donald Wilson, Archie Shepp, etc. lived in North Philly, the Heath brothers from South Philly, Edgar Bateman. I can’t even think of all the guys that lived in Philadelphia at that time. I’m talking about the late 1950s, early 1960s. I grew up in North Philly. When I was living in Philly, there was so many jazz musicians, it was amazing. There were groups of guys. I was part of the North Philly group. There was McCoy Tyner, from West Philly, Bobby Timmons, … The Showboat and Pep’s were the two jazz clubs that everybody was coming to from around the world. Bird worked in another club in North Philly. And that’s where I saw everybody, from Monk, Trane, Miles, Cannonball…

When did you start listening to jazz?

I got married at an early age, when I was 16. I started listening to jazz when I was 17. At that time I was into rhythm and blues. I would sing with a R&B group. One night a friend of mine brought this Charlie Parker album, Charlie Parker Memorial. I remember listening to that record and not liking it. My whole clan of people at the time was into jazz and so I forced myself into listening to it. That’s how I got involved in it.

Did you start playing music at an early age?

I picked an instrument when I was 18. And not only was I 18, I was married and had a wife and kids. I thought it would complement this jazz understanding that was necessary. I picked up the instrument with the thought that in about six months I’d be able to stagger the world. So I got my pop to buy me a horn. I got an alto saxophone. After six months, I could barely move from C to D. I remember trying to practice 15 minutes every day, it felt like all day long. So I put it in the closet. For a year or two. And I had a family and a day job…

How did you get back to it?

It was my day job that forced me to pull it out of the closet because with the job that I had, I was going nowhere with it. At that time, there weren’t many choices. I knew I had this horn in this closet and could make sense out of it. At that point, my whole life changed. I became more disciplined, more purposeful, I used to make myself practice for 4 hours after work every day. Sometimes I’d fall asleep in the chair because prior to that I had not been used to that discipline.

What was your learning process? What was your learning process?

Most of my learning was being around people that knew more than I. I used to go to jam sessions with all these guys of Philadelphia. I developped 3 or 4 years before I went to a club. What I do remember is the first night. I actually wasn’t on the gig. I went to the gig because friends of mine were on a gig. There was Kenny Barron. I played on this one tune. And people applauded. After that, I was walking on a cloud for three days.

Did those musicians help you out?

I remember talking to Odean Pope about my frustration. He was living a few blocks away from me. I was going to jam sessions with these guys that knew more than me and I would sit and sit and sit until they played a tune that I knew and that I could play on. They weren’t interested in teaching me. You figure it out the way I figured it out. Odean said : « What you should do is get some guys that are on your level, form a band and you all can develop together. » I never forgot this. I thought it was so profound. And that’s what I did. The drummer was Sherman Ferguson. He worked a lot. We got together often. And we got together so much that we did some gigs. It moved me up to a point that I could start working with bands.

This lifestyle must have been tough physically?

I was always late on Monday morning because in those days clubs would stay open later. I didn’t have a car and by the time I got home, it was time to get up and go to work. I don’t know how I did it, but I dit it. That went on like that for a couple of years. I stayed on that day job for 8 years.

Was your first professional experience with jazz musicians?

As I was developping I started to work with rock’n’roll and R&B groups. And I was working quite a bit. I was making more money working with rock’n’roll groups that I was making on my day job.

At what point do you meet John Coltrane?

I got this gig at a place called The Last Way Out and this place didn’t serve alcohol. They wanted me to bring a band in there. I brought a quartet with a singer. We used to work 4 nights a week. We did this gig for 2 or 3 months. And I remember telling the guys in the band « When this gig ends, this band is going to end because I’m losing money doing this and I got a family to take care of. » But Coltrane was interested in coming into this club because he wanted to play in places that didn’t serve alcohol. I remember talking to him extensively about the whole thing. I think he felt the music was more spiritual than to have all this noise and alcohol around. At least that’s what I took from him. I played with him once at that place. When the gig ended, I tried to go back to my R&B surroundings and it didn’t work. I was having a hard time.

Is is after this gig that you decided to move to New York?

On my first night at The Last Way Out, I called Kenny Barron. He was living in New York and he came down to make the gig. Kenny heard me for the first time since the jam sessions I used to sit down. He told me I sounded great and that I should go to New York. When The Last Way Out gig ended, I was wrestling with where do I go from here. And I’ll never forget this. Coltrane’s mother used to live not far from me. One night I saw Coltrane on the bus. It was after playing with him and after The Last Way Out gig had ended. I told him I was thinking about going to New York to see what I could do. He said : « You’ll be fine. You’ll do well in New York », and he added « If you ever get the opportunity to play with Elvin, take it. » So when I went to New York, I went looking for Elvin.

What was your relationship with John Coltrane?

Before I played with Coltrane, I had spoken to him a number of times at clubs. When I first heard Coltrane, I didn’t like him. I was into Sonny Rollins. But I remember seeing him in a club in North Philly somewhere in that transtional point from not liking him to falling in love with him. I remember he came outside an intermission one night at a club and I thought he was 9 feet tall. He looked like a giant to me. That’s what I felt. I’ll never forget this, it was on a Friday night, I was at a friend’s house and somebody played My Favorite Things. I got up early that Saturday morning, went downtown, bought the record and played it until it turned brown (laughs). From that point on, I was in love with this guy. And he just got bigger and bigger to me. To the point to where now I miss him. I met a lot of people but I never met someone like Coltrane.

Could you sum up your influences? Could you sum up your influences?

My influence is Cannonball, Sonny Rollins, Eric Dolphy, Sonny Stitt and Coltrane. And that’s it. Those guys played enough to cover everybody.

How did it go when you first got to New York?

I’ll tell you, New York has been good to me. When I came to New York, because I had a family, I couldn’t make a move without being certain of the move. When I got there, I thought I would try for a week or two to see what I could do. Jimmy Murray, who I knew from Philly, told me there was a jam session up at a club called Beefsteak Charlie’s on 52d Street. So I went up there and when I got in, there were all those horns from the bandstand all the way to the doorway. I got in the line and waited. At some point, a guy came in to discontinue the session to announce the featured band that was playing. It ended up the featured band was Jimmy Murray on bass, Jane Getz on piano, Joe Henderson on tenor saxophone, Freddie Hubbard on trumpet, Elvin Jones on drums and Sonny Fortune on alto saxophone. Everybody was wondering who the hell was this guy! (laughs) All I remember is when I finished, the guy at the door gave me my money back (laughs). And Elvin told me he was working at Pookie’s Pub and that I should come down and play with him.

Arriving in New York, did you carry a double life (day job, nightlife)?

I knew a policeman in Philadelphia who had given up his job to come to New York and become an actor. Somehow he was leaving his job in New York to go upstate and asked me if I was interested in his day job. I said absolutely. So I came to New York with a job waiting for me.

What was your daily life like?

I used to hang out all night long, get up early in the morning and do this day job. And I would go down to Pookie’s Pub almost every night.

How did you get into Elvin’s band?

At some point, Frank Foster, who was on the gig with Elvin, said that he had to take some time off to write music for Count Basie’s band and asked if I would be interested in taking his place. I quit my job. And a week or so later, Elvin asked me if I was interested in taking Frank’s job. That’s how I started working with Elvin. And I was working with him the night Coltrane died. It was really spooky. It had been on my mind to call Coltrane the whole time I was working with Elvin to tell him I was working with Elvin, as if he would care. It was so pressing but we were working 6 nights a week… and I still had my family. One Saturday afternoon, I went home to Philadelphia and while I was in Philly I called Coltrane to tell him that I was working with Elvin. Alice told me he was asleep. He died the next day. And I didn’t find out about it until one day we were off and I went back to Philly. Just by chance I ran into Coltrane’s cousins and one of them told me Colteane had died. I couldn’t believe it. I ran home and called Alice. She confirmed he had died. I couldn’t believe it. That really threw me. That Tuesday was so heavy we couldn’t even finish the gig. McCoy and Jimmy Garrison came down to the club… It was just too overwhelming. That was a pretty heavy experience.

What was the impact of his death?

This cat used to pack clubs. But when he started out going avant garde people were there on the first set, after the intermission the place would empty out. They thought he had lost his mind. And there wasn’t nothing I could say about it because I felt he was like my father. And I didn’t qualify to challenge my father. But I felt why would he give rid of that quartet. Coltrane told me he didn’t know why he was so restless. He kept feeling the need to turn things over. And he just moved away from that audience. So when he passed, people didn’t know how to react because there were mixed feelings about his guy. But they shortly recognized, forget these past 2 or 3 years, what he had done. And it all worked out to where it is today.

Which band did you prefer?

I saw him many times. I saw him with his first drummer Pete La Roca in Philly with Steve Davis, then with Elvin and Reggie. I saw the whole band evolve. I prefer the band with Elvin, Jimmy Garrison and McCoy. To me, that was the essence of jazz to today. I tried to put together a band that creates the magic that I saw in that band. That’s what I feel with Dave Williams, Steve John and Michael Cochrane. That’s why I recorded with them my only live album.

What did you like so much about Elvin Jones?

Oh man! Oh baby! Now you ask me a difficult question. I’ll just sum it up by saying he was a magician. He created the magic. To me, music has very little relevance unless it has magic. Otherwise it’s just notes and sound. When I was playing with him in the 1980s, I would play next to him. He always had me standing next to him. I used to say to him « Man, I walk down some of the same streets you walk down, I never heard some shit like that. Where do you get this shit from ! » (laughs). Man, I miss him so much. He was an incredible cat, he really was. I’ve been blessed to meet a lot of unique people, very unique, and these cats that I’ve met from McCoy to Buddy Rich to Miles to Mongo to Elvin, they are very unique. Elvin revolutionized jazz. There’s a slow meter that was never played before Elvin. He had a way of playing that slow groove, you can listen to him playing it all night. I remember one time we went to Istanbul, he went to the Zildjian factory and they gave him some cymbals. He had a crash cymbal. I told him I was going to steal it, he said « Noooo! » (laughs). It was so beautiful. What was so mystical about this guy is that he looked brutal but he had a touch that was very magical. Very magical.

Working with Mongo Santamaria was important. How did you meet him? How much was travelling was there?

Someone in Philadelphia knew him and recommended me to him. I auditioned for the gig and got the gig. We were travelling so much, it put a strain on my family. My wife and I went separate ways. At that time, Mongo was very popular. It was a big band that had a lot of notoriety. Mongo was one the best cats I’ve ever worked for. He paid well. We used to work some of the best gigs. We worked all the time. I worked with him for two and half years. Near the end we would leave New York in January, come back in July, stay a few weeks and leave in October. We went all over the United States and Canada. We used to work in Vegas twice a year a month at a time. That was why we were out so long. A month at the Lighthouse in Los Angeles. In result I moved to California because we were touring a lot in California and also because I’d lost my feeling for New York.

What was your relationship with Mongo’s music? What did you learn from that experience?

I was interested in it because it was Afro-Cuban but I didn’t know a lot about it. To this day I walked away with a lot of information from that experience that I carry with my own presentation. I think my music has a lot of variety because of working with Mongo. I’m always trying to put a Latin piece somewhere or turning something into Latin. Mongo was a hell of a trooper. He was one of those guys, the show must go on. And he would go on. I respected him for that. All these things were a good experience for me. I’ve always acknowledged it. My experience with Mongo was very rewarding for me. But the thing I didn’t like about working with Mongo was doing commercial music. We were doing instrumental commercial music. His version of Herbie Hancock’s tune Watermelon Man was a hit. We went to the studio to record and the producer wanted to do another hit. And he put me on the album. « Cloud Nine » (Stone Soul, 1969) featured me. That kind of gave me some notoriety. And people of the jazz community remembered me for playing with Elvin. So when I came back to New York, six, seven months later, it was a little easier for me having established those kinds of credentials. And I couldn’t fall into the Los Angeles groove. You had to start early because by 9 or 10 pm people were going home…

What was your state of mind coming back to New York?

I came back to New York looking for McCoy.

You really dig that band!

I’m telling you, that band mesmorized me! One night, McCoy was working down at a club in the Lower East Side called Slugs. I went down to sit in. I knew McCoy from a couple of times when back he came to Philly to play in a band that I had been working with in the outskirts of Philadelphia. They would bring in featured artists and hire local musicians. I didn’t know him when he was working with Coltrane. After sitting in, someone called and asked me if I would replace Byard Lancaster for one gig. That night I got a herny because I had moved in, the suitcases, all that… I went to the doctor and he scared the shit out of me. I was in the hospital for six days. McCoy had told me that if I was interested I could have the gig. But I was six weeks in recovery. My first gig after the recovery was with him. After the gig, I went back to the doctor thinking I had a second herny playing with him! (laughs) It was all okay.

Like Elvin Jones, McCoy Tyner is one of those unique musicians.

There’s a lot of piano players but there’s only one McCoy. Today so many people sound like him. It’s like when I discovered Charlie Parker two years after he had passed away. When I came to New York, everybody sounded like Bird. At the time, nobody was playing like Elvin, nobody was playing like Coltrane, nobody was playing like Jimmy Garrison. The miracle of Coltrane’s band was that somehow he brought four individuals together with their own approach and direction and he pulled it together and they came out as one unit. Jimmy Garrison is the only cat I didn’t have a chance to talk to extensively about Coltrane.

After McCoy Tyner, you played with Buddy Rich and Miles Davis. Did you leave Buddy for Miles?

I worked with Buddy Rich for about five months. We were working 6 nights a week in a septet. As far as I’m concerned, Buddy Rich was nothing about just drums. That’s all he was interested in. One night, he had to take off to do the Johnny Carson Show and I got a drummer to replace him. He went all the way to California, taped the show and came back the following night. When we were working 6 nights a week, he would find work on the off nights. He was from that old school. Those cats they don’t know what to do except stay on the road. I never saw any negative stuff about Buddy Rich. And yet I didn’t tour with him. We were getting ready to go on the road and Max Gordon, from the Village Vanguard, came by the club one night and asked me if I would be interested in bringing a band at the Vanguard. He knew me from when I was playing with McCoy at that club. I said yeah. But Buddy’s manager didn’t want me to take off. I had to do this. On the last night at the Vanguard, Miles whispers in my ear « You wanna join my band? », I said : « I’ll be right there! » (laughs). That’s how it happened.

Did you know Miles Davis before working with him?

I did a recording with him before that. And he asked me then to join the band. But I was with McCoy at the time. And I didn’t want to leave him. When I first started playing with him, he had a quintet with me and Woody Shaw. And he broke the band down to a quartet. So he was giving me a lot of room. I didn’t want to leave McCoy to go with Miles because Miles was playing fusion music and McCoy was playing the music I was interested in. When I started working with Miles, one day he asked me why I didn’t join the band in the first time…

At that time you recorded your first album as a leader : Long Before Our Mothers Cried (1974). At that time you recorded your first album as a leader : Long Before Our Mothers Cried (1974).

My first album was in 1965. It was called Trip on the Strip. It was with organ player Stan Hunter. I was playing tenor and alto. We were co-leaders. But my first album as an exclusive leader I was still working with Miles.

You weren’t a fan of fusion music and yet when you worked with Miles, he was doing fusion.

Miles was a hell of a dude. I did four albums with him. Miles was Miles. I didn’t necessarily love the music that we were doing. I had mixed feelings about this. Just like when Coltrane was going avant garde. Miles was a little more easy for me to opinionate because I felt he was moving towards a more commercial endeavour. Coltrane wasn’t moving toward the commercial, he was moving to what he felt was important which is, to me, commitment.

What period of Miles did you prefer?

I prefer the pre-fusion bands. My preference is when Coltrane, Cannonball, Jimmy Cobb and Paul Chambers were in the band. To me, that was the best band Miles had.

A year after the release of your first album as leader, you record Awakening (1975) with Kenny Barron (p), Reggie Workman (b) and Billy Hart (dm) among others. Why did you choose Billy Hart?

I met Billy around 1964-1965 when I was playing with organ players. And I wasn’t necessarily an organ fan. I was a piano rhythm section guy. I was working in Atlantic City with drummer Chris Colombo, Sonny Payne’s father, who had been working at Club Harlem for 30 years. So one summer I went down there. There were organs all over the place. One night on intermission I went to see Jimmy Smith at The Winter Garden. All the organ players were stunned about Jimmy Smith. I didn’t know who he was (laughs). I heard him play « Night in Tunisia », it was so awesome it knocked me clear on the floor. When they came down, I ran over to Billy and hugged him and said how great it was. That’s how I met Billy. So when it came for me to do my thing I knew Barron, from Philly, I had already met Billy, I knew Reggie.

In the early 1980s, you reunited with Elvin Jones. How did this reunion go?

I worked with Elvin for two months after Coltrane died. And I worked with again in the early 1980s. He called me to work with him at the Vanguard. And I went in there playing tenor. I played tenor for the first time with him. Jonesy was a hell of a cat. Strangely enough we never talked about our beginning until one night at Ronnie Scott’s in London. This was about our last year or so of our working together. He used to introduce all the guys in the band and he would say something before he introduced us. And referring to me, he said: « Ladies and gentlemen, this guy here, we’re kind of like brothers. Coltrane told him to come search me out. » And I never recall having that conversation about him. I never talked to Elvin about all of this. I truly miss him. The magic that he brings to a bandstand, I still feel the need to hear that.

In the Spirit of Coltrane (2000), which consists of 7 compositions and 2 covers, is your tribute to John Coltrane. Because of your story, was it difficult to make this album?

It was hard for me to move away from Coltrane. I had already written one tune, « Trane and Things ». And I was having the hardest time writing other compositions. Then it hit me one day. Why are you having all of these problems in your head? This is the easiest music in the world for you to write because you know these guys and you love this music. I sat down and starting to write with that intention. I was looking for something different and didn’t want to sound too much like him and yet I wanted the influence to be there. The reason why I was making this so difficult was because I thought the whole endeavour was attempting to tample on sacred ground. « You know what Coltrane means to you, you’re sure to want to do this? » And it was so much for me to come up to that initially I felt I couldn’t get it. For a few weeks, I could’t get beyond : « Are you sure to want to do this? ». And then it was solved in only one day. You know this guy! You know his music! You can write some stuff. And that’s what I did.

|

|